Photo Courtesy of Venice Documentation Project

The 2018 Biennale, one of the leading architectural exhibitions in the world, has more importance to architect Hala Younes than the prestige factor. As curator of the Lebanese Pavilion, The Place That Remains: Recounting the Unbuilt Territories, she can deliver her heartfelt message beyond her studio, and engage fellow Lebanese and the international community in seeing our surroundings from a new perspective.

The idea of the transformation of the territory, especially the urban sprawl in the Lebanese mountains, is one that architect and Lebanese American University assistant professor Hala Younes has been tackling through research and in her studios with students for years. “The unbuilt – the garden, the road, the public spaces – is also in the realm of architecture,” she teaches. “People do not understand that open spaces are not there to be built but to breathe. You need space to breathe.”

“People do not understand that open spaces are not there to be built, but to breathe.”

When she learned the theme of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia focuses on Freespace, the art of improving the quality of the space not occupied by buildings or constructions, she saw it as an important opportunity to participate in the international discussion on this critical issue.

This edition of La Biennale di Venezia Architettura is bringing together architects and designers from six continents to showcase new projects and hold discussions on the annual theme. It takes place in various locations around Venice, Italy, from mid-May until Nov. 25.

“Lebanon’s participation stimulates the academic debate on urbanism and magnifies the Lebanese architects’ views and contributions on the key topic of the quality of public space.”

Upon learning she had been selected to curate Lebanon’s exhibition, Younes was excited and awed by the challenge. With her project, Lebanon is participating for the first time at the international level in one of the most highly regarded events of its kind in the world.

As the Italian ambassador to Lebanon, H.E. Massimo Marotti, said at a press conference announcing the project: “Lebanon’s participation for the first time will have a double impact. It stimulates the academic debate on urbanism and magnifies the Lebanese architects’ views and contributions on the key topic of the quality of public space.”

Architect Hala Younes, Curator of the Lebanese Pavilion ; Photo courtesy of Venice Documentation Project

The Lebanese Pavilion

The theme of the Lebanese Pavilion is The Place that Remains, taken from Younes’ studio class. The subtitle is Recounting the Unbuilt Territories. The project takes a holistic view of a Lebanese territory, specifically the Beirut River and its watershed, taking an inventory of what remains. It considers the empty spaces – their qualities, their histories and their potential.

Younes has organized a diverse collection of the work of architects, artists, researchers and others that aims to bring attention to the idea that heritage is not only architectural, but also geographical and landscaped. “We are counting on the hope that developing knowledge of the territory in Lebanese society will encourage everyone to defend its value. If you want to take care of something, you have to know it.”

“We are counting on the hope that developing knowledge of the territory in Lebanese society will encourage everyone to defend its value.”

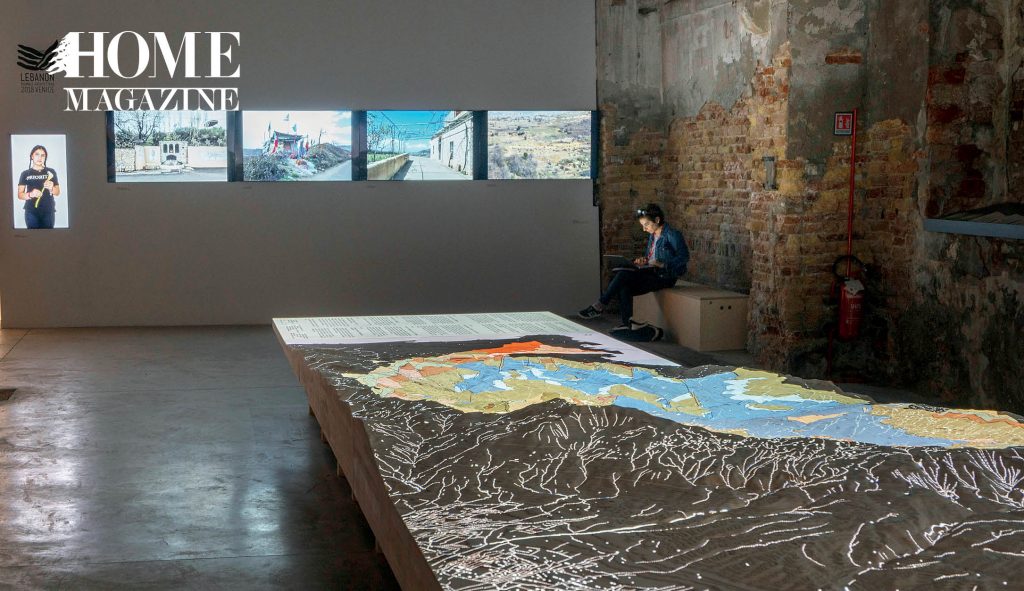

The Pavilion combines a giant 3D relief map of the Beirut River watershed, from the Bekaa to Burj Hammoud, with landscape photography and video surveillance. It features the work of six photographers selected by the curator and professors from the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik and Notre Dame University. The photographers are: Gregory Buchakjian, Catherine Cattaruzza, Gilbert Hage, Houda Kassatly, Ieva Saudargaite and Talal Khoury (video). Historical photographs from various collections are also included, as well as aerial photos provided by the Lebanese Army.

“The photographs are important because they show how the place is perceived,” said Younes. “We know places through our senses – our eyes, our ears, touch, smell, from our culture, what we carry in our minds.”

Each photographer’s work reflects his interest and point of view. One photographer took a series of portraits of Lebanese people in their villages, posing with an object that shows their relationship to the territory. Another photographer documented the traces of agriculture in the territory. Another looked at the relationship between infrastructure for leisure and landscapes.

Younes turned to her laptop and pulled up a photo of a neat, new soccer field with artificial turf and a metal fence that abuts a gaping hole in the side of a mountain. “This photographer documents the gap between the natural landscape and the way infrastructure settles in it. This photograph tells everything. A natural site was sacrificed to create a football field that is now part of our landscape,” she says.

It reminds Younes that “roads here are usually designed in very superficial and technical ways. When you drive, you would like to see the view, but often you have concrete retaining walls that hold the mountain but have nothing to do with the quality of the experience of people traveling those roads. Designing roads should involve architects and skilled designers, in addition to engineers.

“And we have those beautiful old walls that were built stone by stone. Some of them are completely dismantled to put a concrete retaining wall. You feel that you are hurt by this destruction. What’s happening here is irreversible.”

“And we have those beautiful old walls that were built stone by stone. Some of them are completely dismantled to put a concrete retaining wall. You feel that you are hurt by this destruction,” added Younes. “What’s happening here is irreversible.

Since antiquity, Lebanon has been described as a place of amenities and comfort, of beautiful landscapes and views, said Younes. “When you see what it is becoming as the result of uncontrolled development, you realize the importance of conservation as well as preservation.

“We in Lebanon are concerned with the preservation of historic buildings and that’s important, but we have a new monument to consider. Our territory is our last monument; it is the most precious thing we have.

“What do we leave for the next generation? For people who will live here in 100 years?”

“Is it really a right to build? What do we leave for the next generation? For people who will live here in 100 years?”

“The thin lines between the river and me” by Catherine Cattaruzza, courtesy of the artist

Behind the scenes

“Preparing the Pavilion was an enormous task,” said Younes. In a lively interview with HOME, Younes and Claudine Abdelmassih, coordinator of the project and an architect with the Arab Center for Architecture, enthusiastically talked about the thrill of creating the exhibition.

“I started thinking about this one year ago and began talking to people, building a team. Since we began hard core in October, I lost a lot of sleep,” said Younes.

This project was developed with the support of the Department of Urbanism at the Lebanese University, the School of Architecture and Design at the Lebanese American University, the Arab Center for Architecture (LAU) and the Lebanese Landscape Association. The Department of Geography at Saint Joseph University and the Directorate of Geographic Affairs of the Lebanese Army have also contributed significantly to help create the giant territorial 3D model.

“We in Lebanon are concerned with the preservation of historic buildings and that’s important, but we have a new monument to consider. Our territory is our last monument; it is the most precious thing we have.”

National discussions on the theme, The Place that Remains, began in Lebanon in March at a conference at LAU, organized by its School of Architecture and Design and the Department of Urbanism, with the Arab Center for Architecture and the Lebanese Landscape Association. It considered Lebanon’s open space as “a place that can host our dreams and fulfill our expectations, a precious resource to secure quality living through a more meaningful and poetic appropriation of our territories.

Lebanese Pavilion relief map shows densely-built areas in red; in green is the unbuilt space that remains; Photo courtesy of the Venice Documentation Project

Joining the international discussion

“Whenever researchers come to Lebanon, what they really want to hear is about crises. They see us as a war zone,” said Abdelmassih. “We want to bring a different image of our country.

“We want to show the poetry and beauty in our country, that we have people thinking of living in a better place, and building a good country. And we have resourceful people who are working on these problems and have ideas to share.

“Singapore and Monaco have very small places that are very densely developed; it’s not specific to Lebanon. Urban sprawl touches every country.”

“Many countries, especially small countries, suffer from the same problems we do,” said Abdelmassih. “Singapore and Monaco have very small places that are very densely developed; it’s not specific to Lebanon. Urban sprawl touches every country. We can take part in the reflection on these issues.”

For more info:

www.lebanesepavilionvenice2018.com

Facebook: Lebanese Pavilion-Venice 2018

Instagram: lebanesepavilionvenice20188