Interviewed by Editor-in-Chief, Patricia Bitar Cherfan

Disadvantaged, marginalized, impoverished. How does one begin to help people chained to this end of the societal spectrum? MARCH Lebanon is a local non-profit NGO whose mission is to promote social cohesion and personal freedoms through arts and culture.

Lights

MARCH was created in 2011 by a group of people who, simply put, wanted to make a difference. Their first initiatives were largely focused on freedom of expression and anti-censorship, though it eventually morphed into efforts to fight poverty and injustice in the country. In 2015, MARCH took on new challenges and adventures that embrace a diverse set of tools to encourage constructive dialogue and personal development. Peace building and conflict resolution became pillars of MARCH’s work, which continues to evolve and expand its scope of work.

Co-founder and director Lea Baroudi sat down with HOME Magazine to discuss the foundation of MARCH Lebanon as a pedestal for listening and accepting each other’s differences without aiming to silence others in favor of one’s personal convictions.

“We believe arts and culture are tools to bring people together and should not be censored,” she explains. “You can actually, on the contrary, talk about the past and do cathartic processes without having judgment or tensions.”

Baroudi’s eventual work in the field of social activism trying to effectively mend sectarian gaps was an unexpected twist of fate.

“I lived in an apolitical household where we didn’t even differentiate in terms of religion,” says Baroudi. “I began having culture shocks, starting in university when I heard people Sunni/Shia differences, so when we started working on freedom of expression and focusing on youth, I realized how much there were grudges and tensions. People were hiding behind the idea that Lebanon is seen as a beacon for coexistence and acceptance, which effectively, is not really the case.”

With that, Baroudi decided to earn a diploma in mediation at Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth at the Professional Centre of Mediation in Lebanon, which was set up in 2011.

In 2013, after realizing the extent of deep-set tensions and grudges between the sects, particularly in the polarized Sunni-majority Bab el- Tabbaneh and the Alawite Jabal Mohsen neighborhoods of Tripoli, an idea began to formulate around the youth in that area. There’s a certain irony in this, as Baroudi grew up in Ras Beirut and had no prior background with Tripoli. She began considering the possibilities of using theater as a tool to “reconcile people who were at odds with each other.”

“Back then, all you would hear about Tripoli in the media was: clashes, deaths, and terrorism. I was fascinated by the fact that all of this violence was happening in two neighborhoods separated by just one street. I thought that this would be the best place to try this project,” says Baroudi.

“She faced constant pessimism, fear-mongering, and comments like “You’re just a woman. Even a man can’t do that job.”

She was advised on numerous occasions against pursuing this endeavor. She faced constant pessimism, fear-mongering, and comments like “You’re just a woman. Even a man can’t do that job.” Rather than slay her confidence, these words acted as a catalyst for her.

Camera

MARCH’s first project was a play called Love and War on the Rooftop – A Tripolitan Play, written and directed by Lebanese director Lucien Bourjeily. Auditions were held, with 16 youth initially chosen — eight from Jabal Mohsen and eight from Bab el- Tabbaneh. After several long months of rehearsing on a purely voluntary basis, the play premiered to a standing ovation. “The idea was simple,” Baroudi tells us. “To have young men and women from both sides of the frontlines participate in a comedy play inspired by their lives. The more difficult process was to get them to attend the rehearsals. When they did come, they used to come armed. I still remember the very surreal experience of having a garbage bag at the entrance to throw in found razor blades and knives and guns. The mood was very tense,” says Baroudi.

Although she received threats and endured attempts at sabotage, she admits the positive outcomes far outweigh the hurdles it took to get there. From drug addict to administrator, gun-wielder to computer whiz, fighter to advocate against sectarianism, high school dropout to leader of reconciliation, these real-life transformations among participants is what came of Baroudi’s determination.

“With some youth you don’t succeed and others you do. You always feel like you want to stop, but you keep going. At many times, was it hard? Extremely … But when I see these changes in people’s lives and I say what if I had listened at the beginning or what if I had stopped at this point, I wouldn’t see that change. Each one has a part to play,” says Baroudi.

Baroudi’s strength of heart comes from the people and youth with whom she’s worked, but also from the satisfaction that comes with seeing them happy and positively involved with their communities.

“We all think our problems and feelings are the end of the world, but the more you learn of these ordeals, the more you live with your own,” she says.

“Although their view of women is very conservative, they don’t mind women holding positions of authority because it doesn’t shatter their egos.”

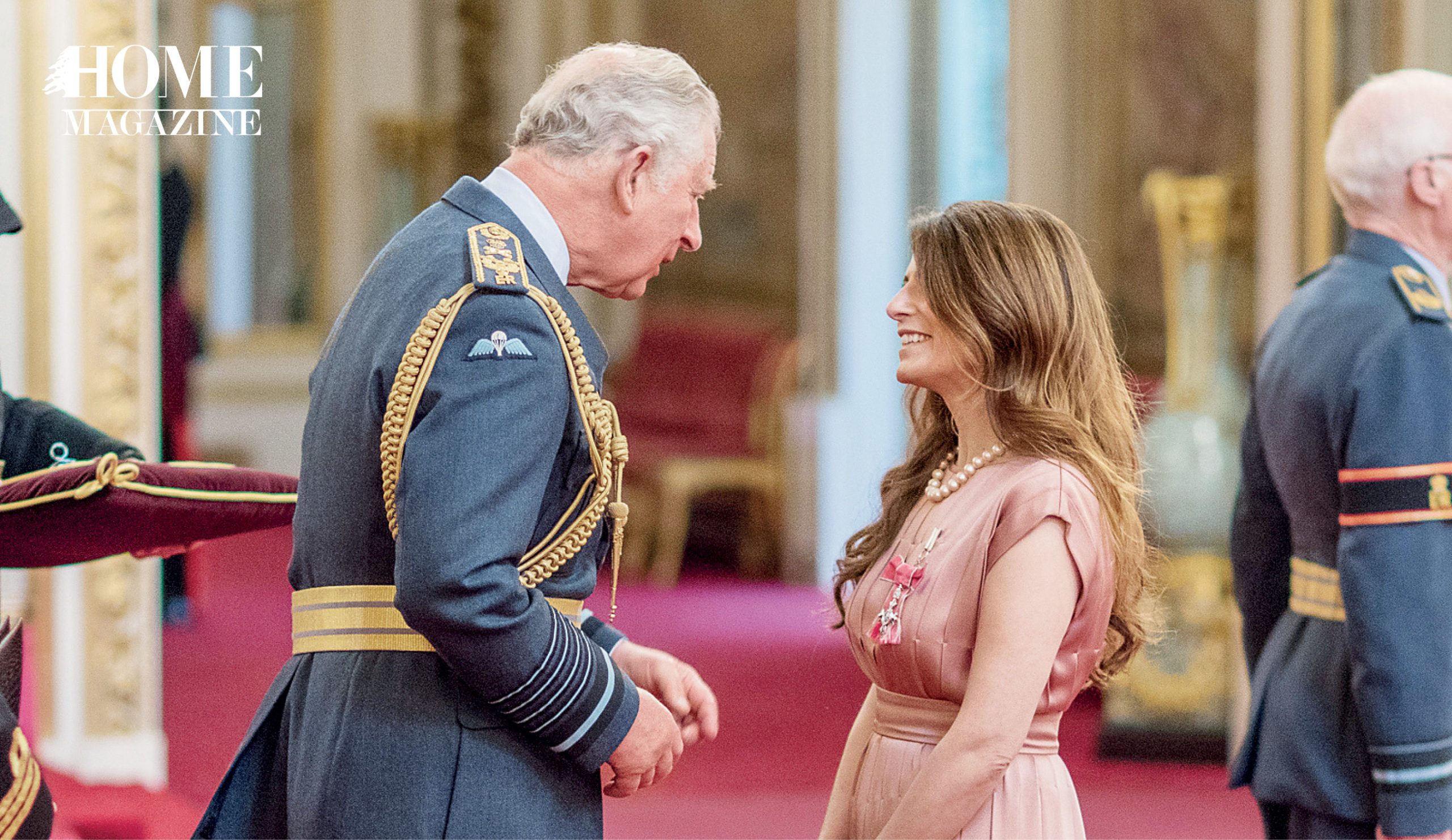

Baroudi, who was awarded a British Order of Chivalry by the Queen of England in 2018 for her work with marginalized communities, laid out MARCH’s key objectives. It aims to educate, motivate, and empower youth, to instill genuine respect and acceptance in the Lebanese social structure, and to strive for women’s rights and gender equality. At this last point, she offered some interesting insight into the psychology and the game-changing dynamic of how being a woman played to her advantage in her efforts to help Tripoli’s youth.

“I think that being a woman made it so much easier. In this very patriarchal environment, because women are not perceived as rivals, they show their weaknesses more easily, and are therefore… more a source of trust. The funny thing is that, although their view of women is very conservative, they don’t mind women holding positions of authority because it doesn’t shatter their egos,” she explains.

Women have different attributes and ways of dealing with difficult issues: talking, connecting, and mediating. Baroudi’s techniques encompass such qualities.

Action

Following the performance of Love and War on the Rooftop, a documentary was released highlighting stages that went into the production, where members from both neighborhoods can be seen laughing and interacting with each other like brothers.

“The root cause of these conflicts and all the violence the youth resort to is not really ideologically based. Of course it’s their lack of hope or tools to change their lives, and they feel the sense of identity loss … In these patriarchal societies, masculinity is very important. It’s either defined by providing for your family or having a nice car, and when they don’t have any of that, violence becomes their way of showing virility,” Baroudi says.

Members worked together to open cultural cafés — one in Tripoli called Kahwetna and one in Beirut called Hona Beirut. This, in itself, is a heartwarming notion, but MARCH took it one step further. They launched a rehabilitation program to allow for these types of free-thought spaces and ideas to flourish.

“In these patriarchal societies, masculinity is very important. It’s either defined by providing for your family or having a nice car, and when they don’t have any of that, violence becomes their way of showing virility.”

Baroudi wanted to provide them with an alternative community space, rather than allow room for extremist groups to seize upon any void in their lives. She initiated a program called Bab el-Dahab, or Gate of Gold, a program built on wellbeing and mental health. Many years ago, the areas of Bab el-Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen were nicknamed Bab el-Dahab because they were very prosperous; Syria Street, the street dividing both areas, had been the pathway for all merchants to travel to Syria. Baroudi set out to restore its former glory.

“First, to the people, it’s a reconstruction project. The idea was to gather the most disenfranchised youth from opposite sides of the frontline — men and women coming from the same environment and the same families. We gave the men basic construction skills: electricity, paint, landscaping, everything. For the women, we taught them graphic design. They did all the signs and marketing material for the shops. Together, they rehabilitated what was destroyed by the war on the former demarcation line,” says Baroudi.

They also participate in side activities. For instance, they help prepare lunches and eat together in the cafés, take anger management classes, English and Arabic language courses, computer workshops, math lessons, team sports activities, and go on cultural outings around Lebanon. At the cultural cafés, a recording studio is also available to train rappers and singers.

“On top of all that, we offer psychosocial support, because a lot of them were traumatized, they went to jail, they fought so they have different levels of post-traumatic stress disorder and so this is a whole program that is built with that in mind … Reconciliation comes naturally,” Baroudi adds. “If you put everything in the right context and you put them in the right environment, they’ll decide for themselves whether they want to reconcile or not.” Since 2017, Bab el-Dahab has helped over 250 ex-fighters so far.

“From drug addict to administrator, gun-wielder to computer whiz, fighter to advocate against sectarianism, high school dropout to leader of reconciliation, these real-life transformations among participants is what came of Baroudi’s determination.”

No one is 100 percent good or bad. We all must fight the urge to be unkind, judgmental, or harsh and strive to bring the best out of the people in front of us. As Baroudi explains, “I believe we’re all connected, and the good or bad comes out because of that connection. We have a collective responsibility to live an impactful life. I think the easy way out is saying ‘I won’t make a difference, it’s too hard.’ So, when it comes to hope in Lebanon itself, I have hope in certain people.”

Hope may be frail, but it’s hard to kill. Pointing fingers and placing blame won’t help the future of Lebanon, but maybe, just maybe, a constructive approach to peacebuilding will.