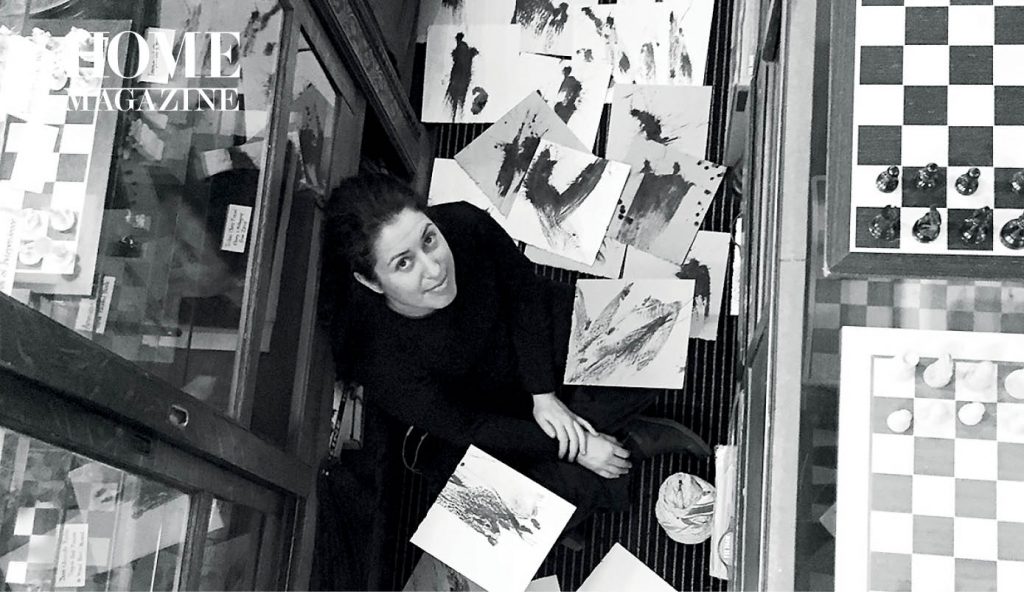

It’s time to start talking about our pain publicly. If we don’t talk, we can’t start the healing,” artist Zena el Khalil told the people gathered to see an exhibition of her work.

Photo by: Imad Khachan

Wearing a long, simple white frock, she stood in the middle of the recently opened Beit Beirut museum in the Sodeco area of Beirut as she prepared to lead a tour of “Sacred Catastrophe: Healing Lebanon,” the first such exhibition held in the newly reopened space that served as a frontline sniper’s nest during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90).

Forgiving, not forgetting

El Khalil’s exhibition was the ideal one to inaugurate the museum’s reopening in September 2017 (it opened briefly to the public in 2016). It is in the bullet-riddled ruins of a building that once served as the Barakat family HOME on Beirut’s Green Line, the center of fighting in the civil war. A sweeping, modern white spiral staircase rises through the three floors of the former HOME, but stepping off it, one is amid sandbags, sniper posts and graffitied walls.

“One almost feels compelled to lower one’s voice and pad reverently though the rooms in deference to the lives that were lost and ruined within and from this building.”

“Buildings are silent witnesses,” el Khalil said as we moved through the rooms, which have been structurally reinforced, but are otherwise much as they were when the war ended. “This building became a killing machine (during the war).” She felt the need to connect to its pain, she said.

“Space without the dark could not hold the stars”

Ash, ink and embroidery on canvas, 2015

Courtesy of the artist and the Giorgio Persano Gallery

Photo by: Josette Youssef

El Khalil said an energy is left behind by the events a physical structure witnesses, and certainly in Beit Beirut there is a constant sense of the building’s bloody history.

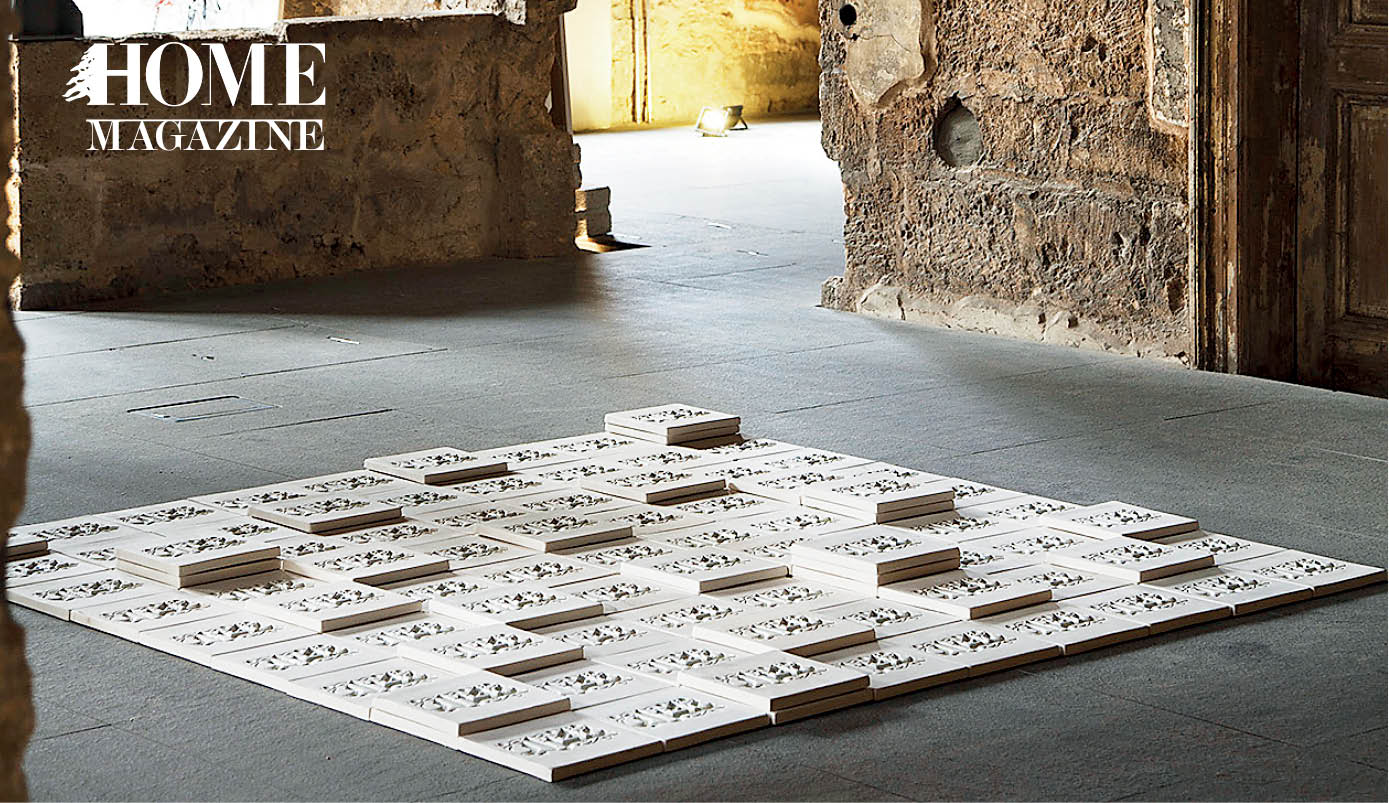

“Forgiveness x 17,000”

Site-specific installation, 2017

Courtesy of the artist and the Giorgio Persano Gallery

Photo by: Josette Youssef

One almost feels compelled to lower one’s voice and pad reverently though the rooms in deference to the lives that were lost and ruined within and from this building.

El Khalil’s exhibition added to this sentiment. As guests wandered through the rooms, they encountered large white canvasses with twisting charcoal-colored patterns. Some of the patterns appeared sinister, as if a wraith were gaining shape from within the canvas to attack; others were almost flower-like and offered an altogether softer, though perhaps more pained, energy.

Each had been produced on site. “I am not a painter who paints in a studio,” el Khalil said.

“Buildings are silent witnesses.”

The more than 20 canvases in “Sacred Catastrophe” were painted in locations in Lebanon that witnessed extreme violence, such as HOMEs that were used by militias, prisons and buildings that were occupied. El Khalil took her materials and traveled to these places, where she began her work by performing a healing ceremony that involved chanting, whirling, dancing and ultimately a purifying fire ritual. It entailed burning some items from the site. She then used the ashes to create an ink, with which she painted.

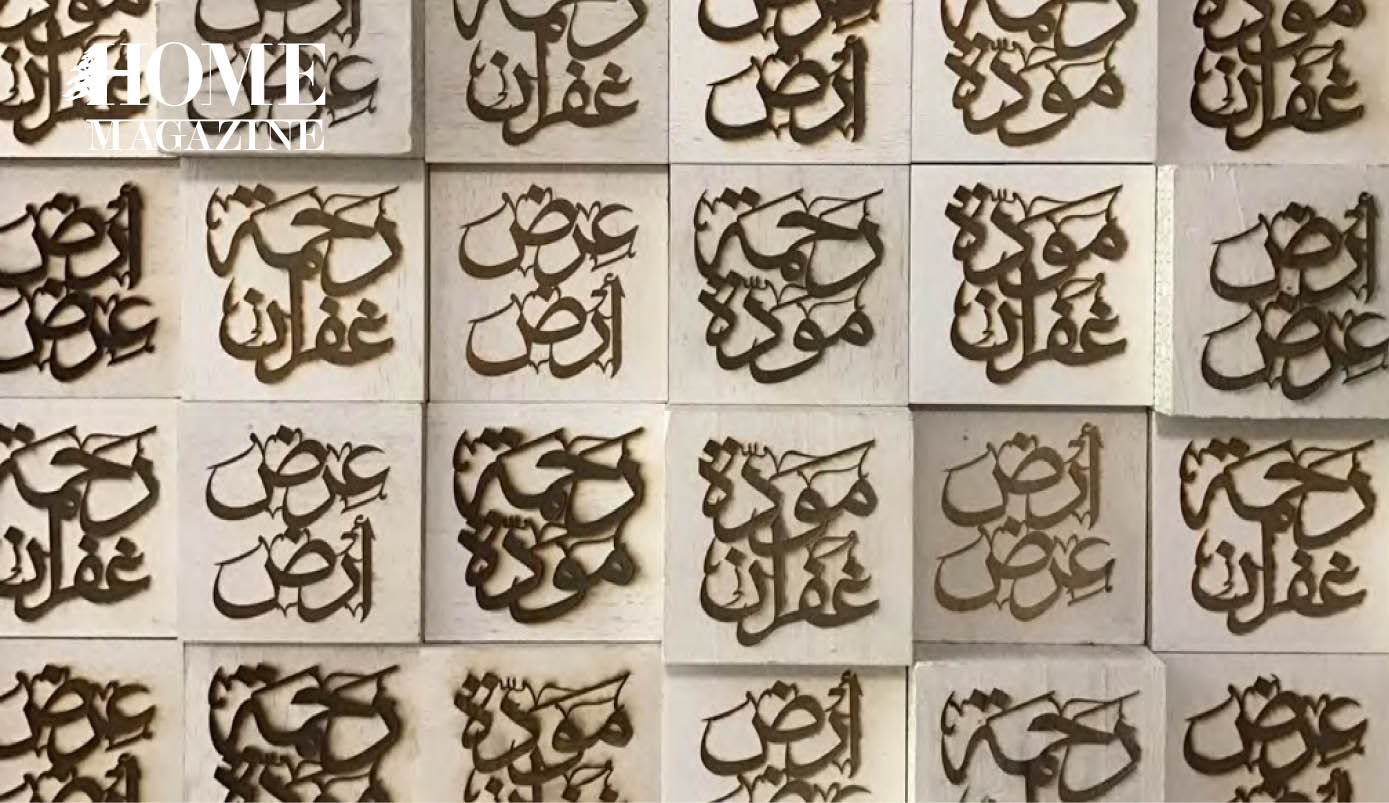

“Gufran (Forgiveness) x 108,”

Ceramic, 2017

Courtesy of the artist and the Giorgio Persano Gallery

Photo by: Josette Youssef

El Khalil — unsurprisingly — used an unconventional method of painting. She used keffiyeh to create the patterns on her canvas, channeling the energy of the place into a physical shape. Lastly, before departing the space, she painted a mantra in the building, choosing one of the four words she had chanted during the healing ceremony: love, forgiveness, compassion or peace. These four words were also reproduced in Beit Beirut.

Her process evolved through her personal experience of returning to her family’s HOME in South Lebanon after the year 2000. The house had been taken, and people were tortured there. She spent hours there, painting with her whole body, flinging herself against canvasses, working out the energy of the space and eventually finding serenity and the ability to forgive.

She performed this whole process in isolation. “To be a vessel, I need to be alone,” el Khalil said. Finding the means to forgive the perpetrator of atrocity — and heal the victim — is possible “if we can learn not to think of ourselves as victims, if we can use catastrophes as opportunities to grow.”

“Everyone goes to war for the same reasons — love or power.” El Khalil told a story. A sniper was asked, why did you pull the trigger? His answer was simple. “Love — out of love to protect my family, my HOME.”

” A sniper was asked, why did you pull the trigger? His answer was simple, “Love — out of love to protect my family, my HOME.”

“Everyone has his set of trauma,” she said. What makes the difference is how one approaches the process of reconciliation.

“I think we’re ready now to do the work to move on. If we plant the seeds of reconciliation, we transform the generation to come.” Much of that reconciliation lies in abandoning guilt and instead apologizing, she said.

“Sacred Catastrophe” is already serving as part of that reconciliation process.

During its 40-day run at Beit Beirut, it brought people from across the city into the space for events that ranged from tours to talks to storytelling nights to meditation sessions, and spread el Khalil’s distinctive method of healing.

Her unique message of compassion and forgiveness doesn’t entail any forgetting of the past. In fact, it makes the past more visible.

Photo by: Yarob Marouf

During the exhibition, el Khalil’s installation art piece “17,000 x Forgiveness” sprawled across two floors, taking up the majority of Beit Beirut’s exhibition space. The piece was comprised of 17,000 green lines, one for each of the 17,000 people declared missing during the Lebanese Civil War, making tangible the sheer scale of the number of individuals and families affected.

“I love you without wanting anything back.”

In the background, a poem el Khalil wrote played on a loop, charting her personal path to coming to terms with such trauma and showing a way to others ready to follow it. It circled beautifully around one line: “I love you without wanting anything back.”

For more info: http://zenaelkhalil.com/healinglebanon