Interviewed by Editor-in-Chief Patricia Bitar Cherfan

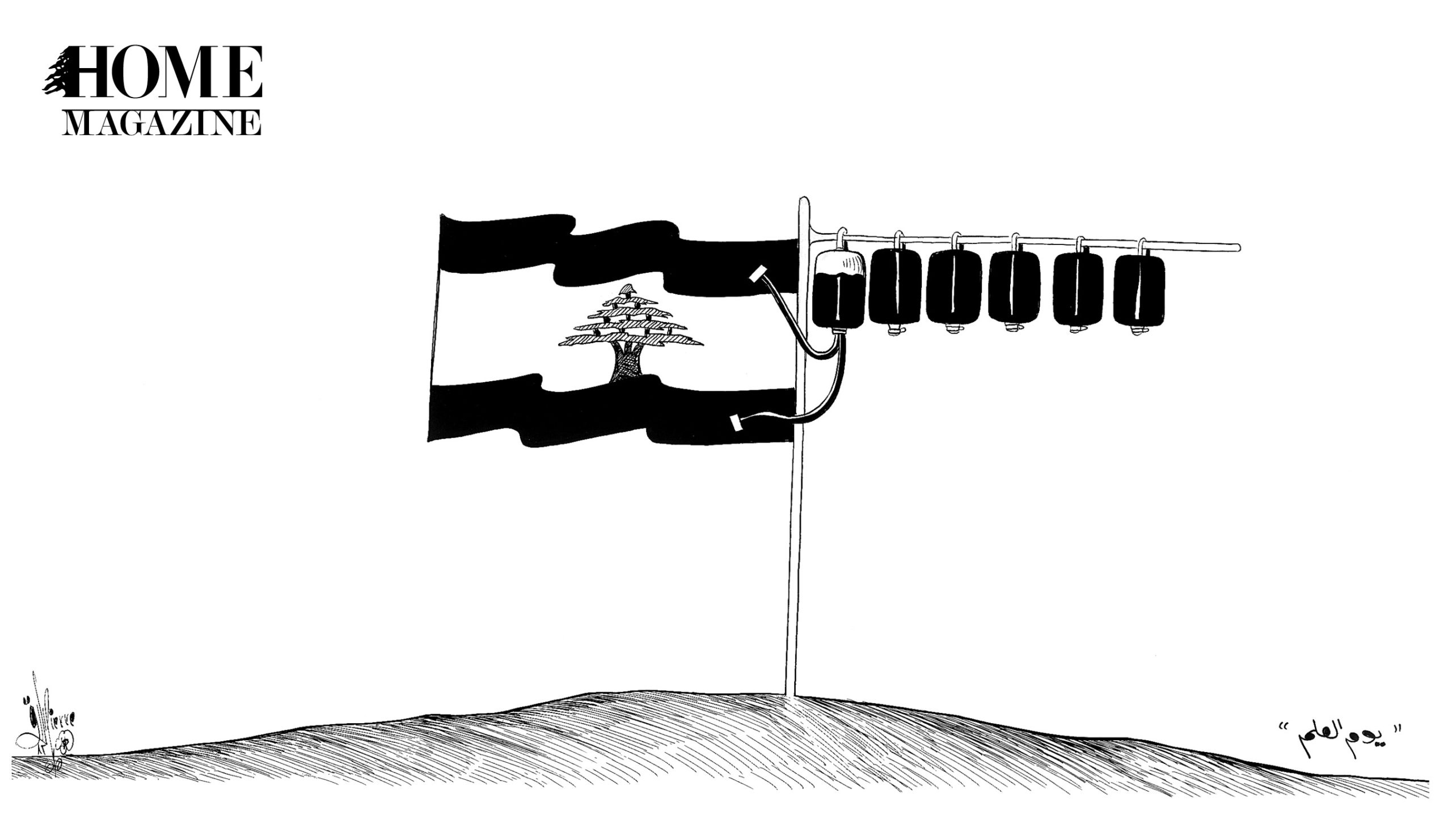

A staunch supporter of freedom of speech, Pierre Sadek channeled his acerbic critique of politicians through his tireless pen. Ghada Sadek Abela, the daughter of the late caricaturist and president of the Pierre Sadek Foundation, opens up about her father, his legacy, and the efforts being taken to preserve it.

Televised, daily cartoons were not a thing until a renegade artist by the name of Pierre Sadek entered the scene. From 1986 until 2013, he animated caricatures accompanied by a catchy background jingle that were the staple for the average Lebanese household. “Frame by frame, Pierre would draw his animations which somebody would then animate for TV stations, LBCI andFuture TV,” says Ghada. By disrupting the status quo, Sadek spoke to and for an entire nation whose frustrations needed acknowledgment as well as a platform to vent their understandable rage.

Born in Zahle, Sadek spent his life in Lebanon — a country which, for all his criticism, he felt a deep attachment toward. As a youth, Sadek’s teachers recognized his artistic talent while his parents tugged in the opposite direction, fearing that the pursuit of this path would leave him penniless. Overstepping his parents’ advice, Sadek resorted to clandestine measures to achieve his artistic ambitions. “His parents thought he was studying business. Instead, he was secretly studying the arts at Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA) and covering his tuition fees by illustrating flowers for seamstresses or writing newspapers headlines,” says Ghada. Caricatures became Sadek’s preferred medium to channel his frustrations, challenge the political elite, and mock the daily idiocies committed by the powers that be. “While Egypt was more open to the art form in those days, In Lebanon, this field was still in its infancy,” says Ghada.

“Pierre spoke to and for an entire nation whose frustrations needed acknowledgment as well as a platform to vent their understandable rage.”

Fame recognized Sadek’s talents early on, catapulting him into the public eye at a young age. Politicians respected yet feared the brutal honesty that came unfurling from his ruthless pen. What was it about this caricaturist that kept everybody on their toes? By age 20, King Hussein of Jordan sent the young talent a private jet for a commission of a caricature of Abdul Nasser for what was then a generous commission of 500 liras. Interestingly, Abdul Nasser changed the itinerary of the Egyptian airlines so that he would reach his destination in time to keep up with Sadek’s latest piece and the political editorial of the late Michel Abou Jaoudé.

The seminal years of his career were spent at the leading newspaper, An-Nahar. “The paper taught him everything,” says Ghada of her father’s 21- year history with the publication. Famed journalist, Ghassan Tueini, and Sadek formed one of the region’s most revered teams. Sadek pioneered the daily eight columns on the last page of the newspaper; no illustrator had enjoyed such visibility or privilege thus far. “Newspaper vendors started to fold An-Nahar in such a way that the last page with his drawings would be visible to customers instead of the first page,” says Ghada.

Over the years, Touma — a pot-bellied old man in traditional wardrobe brought to life by Sadek’s pen in 1978 — became the artist’s mouthpiece. Soon, the character became synonymous with the average Lebanese citizen whose disappointment with their own nation has morphed into satirical detachment. After a long-lasting professional relationship, Sadek left LBCI in 2002.

“The Washington Post offered him a job which he turned down — he did not want to draw American politics. He didn’t want to leave Lebanon. He had survived the war, the shelling, the bombs … only to leave now?” says Ghada. Instead, he went to Future Television who gave him free artistic reign, even allowing him to critique former late Prime Minister Rafik Hariri whenever he wanted to.

The late former prime minister and Sadek shared a close friendship. Hariri’s assassination in 2005 left Sadek infuriated, triggering a merciless attack that spared nobody. According to Ghada, his attitude, since the beginning of his career, could be summed up as such, “I am friends with all and I am free to criticize all.” He fought for the freedom to draw whatever he pleased and speak his mind freely and without censorship. “Either it goes down as is or don’t print it,” says Ghada of her father’s modus operandi.

Despite Sadek’s hard-headedness, he was not foolish and “recognized his freedom but understood the red lines.”

In a country where freedom of speech remains contested, openly expressing dissent can have its consequences. While article 13 in the Lebanese constitution states the following, reality tends to differ: “The freedom to express one’s opinion orally or in writing, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, and the freedom of association shall be guaranteed within the limits established by law.”

In 1968, Sadek was dragged out of bed and thrown behind bars for an illustration poking fun at the undercover military regime, the Military Second Bureau. A kidnapping attempt in 1975 impeded Sadek from working with An-Nahar newspaper and precipitated a two-year hiatus from drawing.

“Newspaper vendors started to fold An-Nahar in such a way that the last page with his drawings would be visible to customers instead of the first page.”

At the altar of fame, we are always curious to know what qualities allowed this person to reach the heights of success. “Pierre had a winning combination of traits. He was cultured, ambitious, felt a deep sense of responsibility, had integrity, and remained very modest throughout his career,” says Ghada. “As an avant-gardist political analyst, he read across the press and could predict future events.

He had a very active social life; he loved people and going out. However, he didn’t like for anyone to be around him when drawing. No music, no people. Just him and his pen.”

An aggressive strain of lung cancer marked the final chapter of his life. “He never stopped creating while doing chemotherapy. He would ask for the treatment to be administered into his left arm instead of his right one so that he could continue drawing,” says Ghada.

At age 74, Sadek passed away. The public saw his death as a major loss. “Countless people came to mourn him — many of which we didn’t even know. Sadek touched and changed the lives of a lot of people,” Ghada says.

Now deceased, his legacy lives on through the Pierre Sadek Foundation. “We did not wait to begin this project. Memory is short-lived — especially in this country,” says Ghada. In 2014, one year after his passing, his family inaugurated the Pierre Sadek Foundation which archives 30,000 illustrations born over a legacy of 53 years. “My mom, Hanan, collected all of Pierre’s originals over the years. She was the engine behind the foundation,” says Ghada. “I feel like my brothers, Omar, and Walid and I are little Pierre Sadeks, carrying on his life’s work,” says Ghada.

“I am friends with all and I am free to criticize all. … Either it goes down as is or don’t print it.”

Pierre Sadek

“We did not want to sell his work and make a fortune,” says Ghada. “Instead, we want to safeguard his work and introduce it to new generation. You can understand the entire history of Lebanon and major events in the region through his work.” Since the foundation’s inception in 2014, Ghada has been high in demand to give lectures at universities and cultural centers across the country.

The foundation launched the Plume de Pierre in 2017 — a yearly competition that reaches 1,500 students across universities in Lebanon. Since 2018, the independent award invites non-students to participate as well. The winners of each category fly to Paris to exhibit in a major exhibition for caricatures in collaboration with Ecole Estienne-Paris and Presse Citron exhibition.

“Touma became synonymous with the average Lebanese citizen whose disappointment with their own nation has morphed into satirical detachment.”

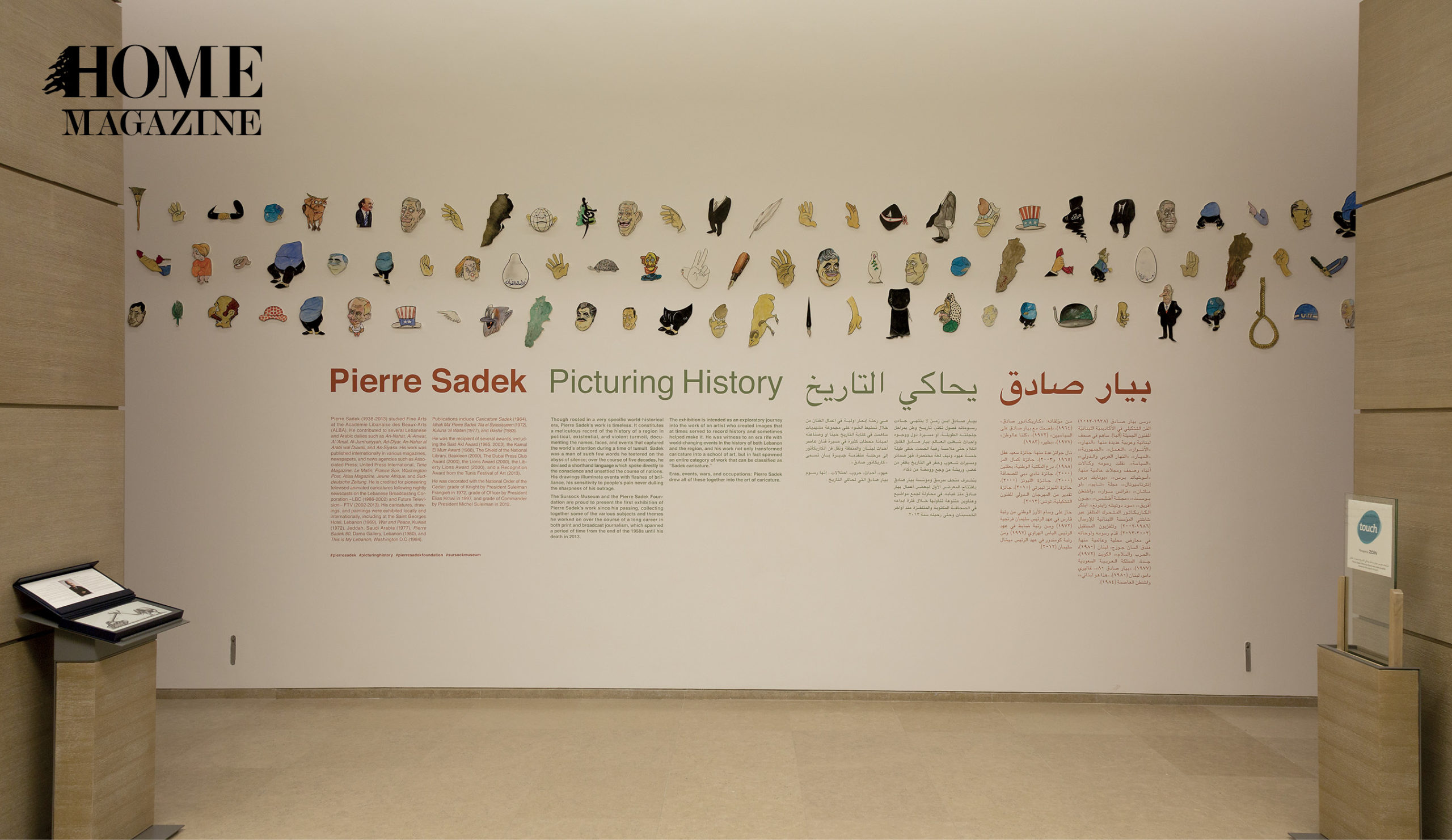

The foundation held “Pierre Sadek, Picturing History” in 2018, a retrospective exhibition held at Sursock Museum and Beiteddine Festival where 700 of Sadek’s caricatures were unveiled to an estimated 40,000 visitors in total.

“This was only 2 percent of his archive,” says Ghada.

“Let us be inspired by the late artist who refused to ever be bought or sold.”

At the time being, the foundation launched the Lebanese Caricature Society — the first of its kind in the country. “We want to introduce new opportunities to artists, to exhibit their work and to support them. We also want to give workshops to schools,” says Ghada. One thing is certain: Sadek has left a permanent impression and will be lasting influence on everybody, from the disaffected citizen seeking out a relatable character on which to project their frustrations to the aspiring caricaturist looking for a supportive platform to kickstart their artistic career through his foundation. In this climate of commodification, where everything — including one’s principles — is for sale, let us be inspired by the late artist who, as his daughter aptly describes him, “refused to ever be bought or sold.”