Banknotes — those bills that we use on a daily basis. When accustomed to their use, we don’t need to read their value, we recognize them from their size and color at a glance. We therefore rarely take the time to really look at them and try to figure out their symbolism through what is depicted on them.

The release of new banknotes by the central bank of any country is based on a long process. Many characteristics need to be considered, including paper type, color, design, security, and so forth.

In 2013, the European Central Bank started gradually introducing the second series of euro banknotes, called the Europa series. They started circulating the €5, €10, €20 and €50 between 2013 and 2017, while the €100 and €200 were released on May 28, 2019, hence completing the Europa series.

The Europa series — not the Europe series — are the new banknotes of the European Union.

Europa, the consort of Zeus in Greek mythology, after whom the continent Europe was called. Two of the Europa series’ security features represent the portrait of Europa: the watermark and the hologram.

The Rape of Europa, Titian, ca. 1560-1562, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, USA.

The Rape of Europa, Titian, ca. 1560-1562, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, USA.

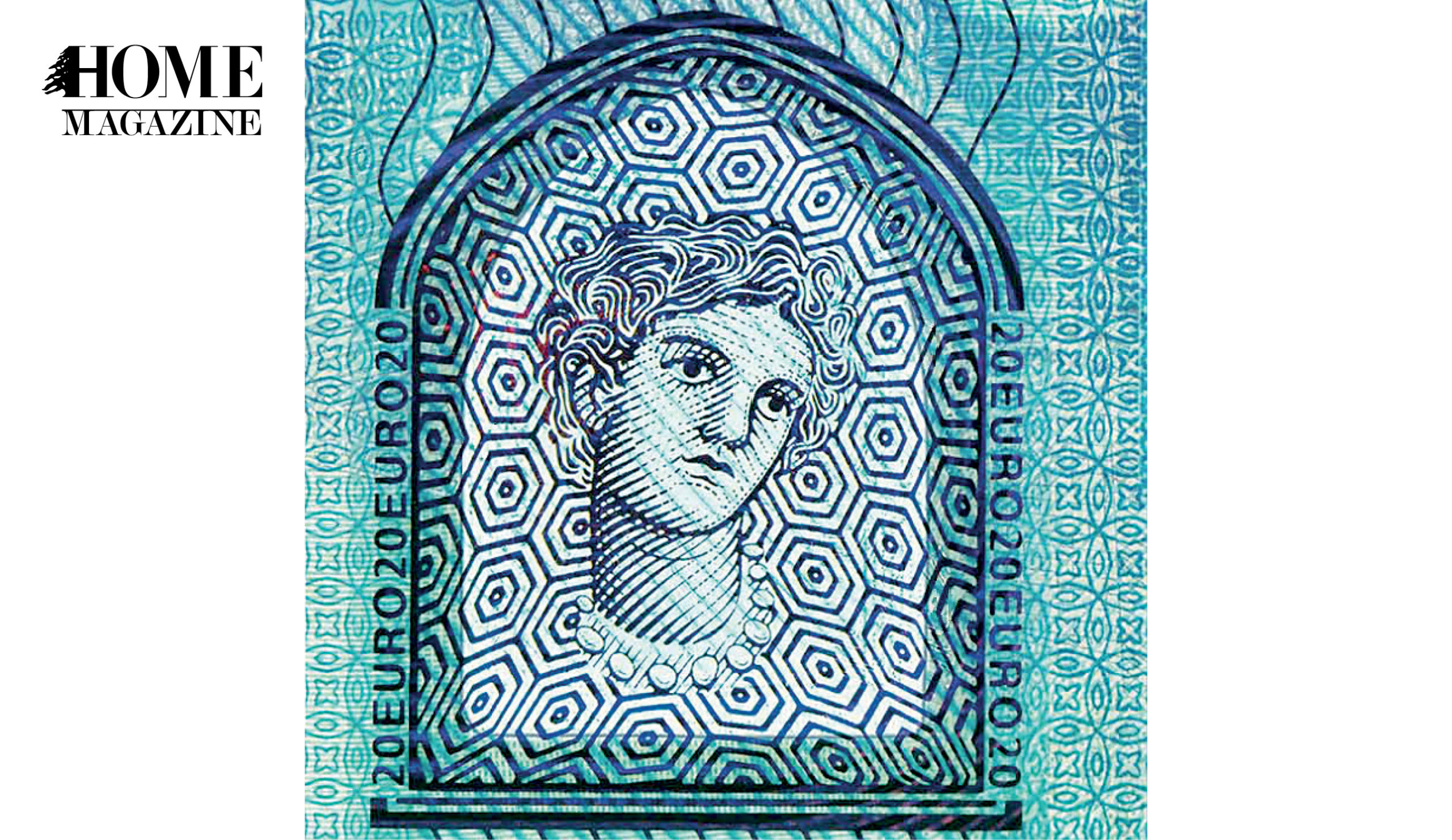

The watermark and the hologram are visible on both sides of the banknote. When holding the banknote against the light, the faint image of the watermark becomes visible, while when laid on a dark surface, the dark areas of the portrait become darker. As for the hologram, it is a transparent window on the banknote containing the portrait of Europa.

The portrait shown on the banknotes is based on an illustration of a mythological scenery, featuring Zeus and the princess Europa, daughter of the King of Tyre, in the form of a bull. The scenery is depicted on a Greek vase found on an excavation site in Italy and is dated to 360 B.C. The vase is currently on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

From a princess to a continent

The myth is the one of princess Europa, who was the epitome of feminine beauty on earth — at least according to the legend — god Zeus who ruled as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus once saw the princess on the shore of Tyre, playing and gathering flowers with her attendants. Despite being married to the goddess Hera, Zeus was captivated by Europa’s beauty and overwhelmed with desire for the mortal princess.

Yelding to temptation, Zeus headed to the shores of Tyre but not before metamorphosing into a magnificent bull so as to disguise himself from his jealous wife.

Watermark Portrait of Europa on the €5 banknote

Watermark Portrait of Europa on the €5 banknote

Ovid, a Roman poet (43 B.C. to 18 A.D.) describes the bull as follows in his poem, Metamorphoses:

In color he was white as the snow that rough feet have not trampled and the rain-filled south wind has not melted. The muscles rounded out his neck, the dewlaps hung down in front, the horns were twisted, but one might argue they were made by hand, purer and brighter than pearl. His forehead was not fearful, his eyes were not formidable, and his expression was peaceful.

Fascinated by its handsome flanks and gentle demeanor, the princess approaches the bull, shyly caressing him. She even holds flowers up to his glistening mouth. The bull lies down at Europa’s feet on the yellow sand, encouraging and reassuring her. The royal virgin grabs his horns, and dares to sit on the bull’s back.

As soon as she was seated, the bull ran toward the sea, and carried the princess away from the shore of Tyre. Looking back at the shore, she was terrified but dared not jump off.

Zeus and Europa reached the shores of Crete, where the god reveals his true identity. Three sons are born from the union between Europa and Zeus. A while later, Europa marries Asterius, King of Crete, who adopts her sons and makes her the first queen of Crete.

Meanwhile Agenor, her father, orders his sons to search for her in every corner of the earth, and commands them not to return without Europa. The sons’ quest is in vain, so neither of them return to their HOMEland. Each son settles in a different region and founds a new civilization: one of them in Thrace (today partly in Turkey and Greece); the other in the island of Thasos; the third in Africa; and the youngest, Cadmos, founded a town to which he gave his name, Cadmia.

From myth to reality

Could the myth of princess Europa be the founding story for what is today known as the European continent? This question has long been asked by historians. Although they have very divergent opinions on the matter, the Abduction of Europa can still be found on ancient coins, in literature, in mosaics, and paintings (e.g. The Rape of Europa by Italian artist Titian), and so on.

Hologram Portrait of Europa on the €20 banknote

Hologram Portrait of Europa on the €20 banknote

In Book 5 of The Persian Wars, Herodotus, a Greek historian of the fourth century B.C. recounts:

Now the Phoenicians who came with Cadmus, and to whom the Gephyraei belonged, introduced into Greece upon their arrival a great variety of arts, among the rest that of writing, whereof the Greeks till then had, as I think, been ignorant.

Europa and her brothers settled in different regions of Europe. This myth should remind us that we all have a common heritage, and that we are, above all, humans — wherever we live, and whatever background we happen to come from.