Interviewed by Editor- in-Chief, Patricia Bitar Cherfan

Renowned oncologist Dr. Elias Jabbour is pioneering developmental therapeutics research in leukemia. The Lebanese American is a professor in the Department of Leukemia at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, a leading cancer hospital in the United States. HOME had the wonderful opportunity to sit with Dr. Jabbour during his latest visit to Lebanon to bring you an inside look at what drives his success.

“War taught me many things,” reflects famed Lebanese-American doctor Elias Jabbour, M.D. As a boy in war-ravaged Lebanon, he saw a neighbor die in front of his eyes from “a random shooting typical of civil war. I realized how fragile life is and that we are granted nothing in this life,” he wrote.

As a leading oncologist working in one of the top cancer centers in the United States, he is reminded of that lesson daily. In a recent interview with HOME, Dr. Jabbour explained how encounters with death, dedicated role models and courageous patients have inspired him to live life to the fullest every single day. For him, that means impacting humanity on a bigger scale, well beyond securing a good future for himself and his family.

Life at full throttle

Jabbour studies both acute and chronic forms of leukemia. He has conducted clinical trials that led to the approval of numerous leukemia medicines and has authored and co-authored hundreds of peer-reviewed articles in medical journals, as well as served on the editorial boards of several scientific journals.

In his office at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where the 47-year-old professor in the Department of Leukemia conducts research and practices clinical medicine, Dr. Jabbour has four computers. “I work on ideas in parallel,” he explained. “I split my days in a way to help me process multiple things. So, I do two days of consultation per week and two full months of hospital duties per year, while the rest of my time is reserved for clinical research.”

I want to make cancer history. I believe in it. I believe we can reach somewhere.”

“My goal is not to have my name on countless publications,” Jabbour said. “It is to impact human life. I want to make cancer history. I believe in it. I believe we can reach somewhere.”

Indeed, he has. “When I first started out years ago, the survival rate for Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia was around 10% only,” he recalled. “With medical progress, it has now risen to around 40% in countries like Canada. Using the current protocol I am applying for my patients, we reached a survival rate of 83%.”

While those results are exciting, Jabbour aims to have broader impact. “My ultimate mission would be to work strategically with the World Health Organization, for example, on how to improve human life, starting with simple things that can make a long-term impact like better eating or water quality,” he said.

” When you accept the reality that your life will come to an end, all you can do is live in the best possible way and not think twice about giving your all in whatever you do.”

At the same time, he wants to change the lives of each patient. Youthful-looking, with just a dusting of gray in his hair, Jabbour speaks passionately about his mission as a doctor. “My goal is to provide the best care, the safest treatment based on evidence—period.”

When asked about his constant proximity to death, he answered: “Through my work, I discovered how fragile human life is. When you see someone die in a second, when you accept the reality that your life will come to an end, all you can do is live in the best possible way and not think twice about giving your all in whatever you do.”

Influenced by role models

Jabbour grew up in a traditional Lebanese household in Zahlé in the Bekaa Valley. His family emphasized the importance of academic excellence. He went to school at the Collège des Sœurs des Saints Cœurs in Rassieh. “We did not have the things today’s children take for granted, like electronics, and there weren’t many outings aside from regular family gatherings every Sunday,” he told HOME.

Jabbour’s godfather, Dr. Joseph Jabbour, a cousin of his father, was a doctor who had studied medicine in France before coming back to work in Lebanon.

“As a surgeon, he used to offer people free consultation. He was wise but also humble and simple. The sense of service I saw in him was the first thing that inspired me to become a doctor,” said Jabbour. “It was clear in my mind. I only wanted to be a doctor; I did not consider any other option.”

When going down to Beirut to pursue his studies for the French baccalaureate in order to subsequently study medicine turned out to be impossible due to the ongoing war, Jabbour sat for the exam as an individual candidate. “I had no option than to rely on my personal efforts. I studied hard and passed my baccalaureate with honors,” he said.

With this step completed, his parents wanted him to apply to study in Montpellier, France, which he did. But meanwhile, the Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth reopened after the war, so the 17-year-old aspiring doctor, who preferred to stay in Lebanon, decided to sit for the difficult medical entry exam. His plan worked perfectly when he finished 11th among 1,200 applicants.

A personal experience motivated Jabbour to specialize in oncology and led him to his second role model. “My aunt’s husband had lung cancer. He was cared for by Dr. Georges Chahine.

“Given my close relationship with my aunt who often, along with my mom, took care of me as a child, his name stuck in my head.”

When Jabbour went on to pursue his residency at Hôtel-Dieu Hospital, he had the chance to work alongside the respected oncologist, Professor Chahine. “I loved the caring way Dr. Chahine looked at his patients,” Jabbour said. Chahine became his mentor and later the godfather of his son. “He is like family to me,” Jabbour said.

“A patient puts his life in your hands, his trust and faith in you. It is an extraordinary privilege and a huge responsibility at the same time.”

Jabbour met his third role model when U.S.-based Lebanese-American hematologist/oncologist Dr. Hagop Kantarjian was visiting Lebanon. Kantarjian is currently the chair of the Department of Leukemia at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. “He was a huge figure, exceptional by all means, but also was extraordinarily humble. When we met, I told him that one day I’m going to work with him,” Jabbour recalled.

After his residency, Jabbour travelled to France to pursue a fellowship at the Institut Gustave Roussy, a premier European cancer treatment center. “I wanted to get a solid Franco-Anglophone training, as I was planning to come back and work in Lebanon. When I finished, I moved directly to the U.S.,” he told HOME. “What I learned in France was great, but when I started working in the U.S., it was like moving from a pool to an ocean. It was on another level.”

After his stint at MD Anderson, he was planning to come back to Lebanon with his wife, Hind, whom he first met in Lebanon and later married in France. Jabbour had hopes of kick-starting a career in his HOME country and accepted a position at AUBMC. Unfortunately, his plans were disrupted, first by the 2006 war and later by the conflicts of 2007. So, he decided to stay in the U.S.

When he applied for the green card on July 14, 2007, he received it in just four days. He received “an accelerated green card” based on “extraordinary ability.”

“It meant a lot to me to be going to a place where you are appreciated for your value and not ‘wasta,’ or who you know,” he said. “You get what you deserve in the United States.” That motivated Jabbour “to give 100 percent to both my patients and my research at the MD Anderson Center.” His hard work resulted in him rising through the academic ranks much faster than the norm, becoming a full professor in just nine years.

“MD Anderson opened the door to me; it was up to me to prove myself,” he said.

Learning from a courageous patient

Perhaps the most influential role model in Jabbour’s life was one of his patients. In an essay, Jabbour described George, a patient he treated at MD Anderson in 2010, who taught him to live in the day. George had AML, a type of cancer that requires immediate, aggressive intervention, but rounds of high-dose chemotherapy failed to bring him into remission. Only in his late 30s, George was a prime candidate for a bone marrow transplant. When he relapsed after the transplant, his prognosis was very poor, Jabbour wrote. Yet George never lost hope.

George lived two more years. He insisted on attending his son’s graduation. Jabbour was able to adjust his treatment and provide the palliative care George needed to be in good shape on that special day. Just before George died, Jabbour sat with him and held his hand. George told him about how meaningful the family events of the past two years had been, how much he and his wife had learned and how much he appreciated the good medical care he had received.

“What set George apart from other patients battling cancer—and people in general—is that most project their plans into the future to forget what is happening today. They will say, ‘When I’m cured, I’m going to go to Hawaii with my wife for example.’ By contrast, George would say, ‘Let’s have a great day today and have faith that we’ll find some other treatment tomorrow. There’s no reason to be upset. Tomorrow will come. Let’s focus on how we can make today better.’

“I learned from him to have confidence and hope, to never give up,” Jabbour told HOME. “But to accept defeat, if it comes. When you lose, lose with dignity.”

Story ends here. What follows below is a separate, related piece to be treated as a sidebar or separate piece following the main story.

A few random thoughts

HOME asked Dr. Jabbour to share a few thought on work, Lebanon and life. Here’s what he had to say.

On work

“Khalil Gebran wrote about how you should work for others as if you’re doing it you’re your lover. I really believe in that”

“And what is it to work with love?

It is to weave the cloth with threads drawn from your heart, even as if your beloved were to wear that cloth.

It is to build a house with affection, even as if your beloved were to dwell in that house.

It is to sow seeds with tenderness and reap the harvest with joy, even as if your beloved were to eat the fruit.

It is to charge all the things you fashion with a breath of your own spirit,

And to know that all the blessed dead are standing about you and watching.”

وما هو العمل المقرون بالمحبة؟”

هو أن تحوك الرداء بخيوط مسحوبة من نسيج قلبك مفكراً أن حبيبك سيرتدي ذلك الرداء

هو أن تبني البيت بحجارة مقطوعة من مقلع حنانك وإخلاصك مفكراً أن حبيبك سيقطن في ذلك البيت

هو أن تبذر البذور بدقة وعناية وتجمع الحصاد بفرح ولذة كأنك تجمعه لكي يقدم على مائدة حبيبك

هو أن تضع في كل عمل من أعمالك نسمة من روحك، وتثق بأن جميع الأموات الأطهار محيطون بك يراقبون ويتأملون”

“Although I accomplish more under stress, you can’t work non-stop without breaks to allow moments of clarity. Moments of inspiration often occur in quiet moments.”

“I always start with a rough draft, then make it better.”

“I like critiques, it makes me grow.”

On reading

“I make sure to dedicate time for reading notably at night or on a plane.”

On teamwork

“My success is a result of team work. My wife Hind has been a constant support since day one. Our success is shared; we are one team.”

“In Lebanon, the approach to success is much more individualistic than in the United States. I have around 30 people on my team and I always make sure to credit them in my success. We succeed together as opposed to pulling each other down.”

On educating children

The Jabbours have two children: Joey, 15, and Scarlett, 6. “Both of them were born in the U.S., but we made sure to give them a trilingual education in English, French and Arabic, like the one we received.”

On living in Lebanon

“My wife loves Lebanon and I was very serious about getting the best training abroad to come back and build a career back HOME.”

“It is not easy to be away from aging parents but being abroad has helped me amplify the impact of my work.”

“Living abroad helped me see the world from a different angle and put me in a better position to help my fellow Lebanese.”

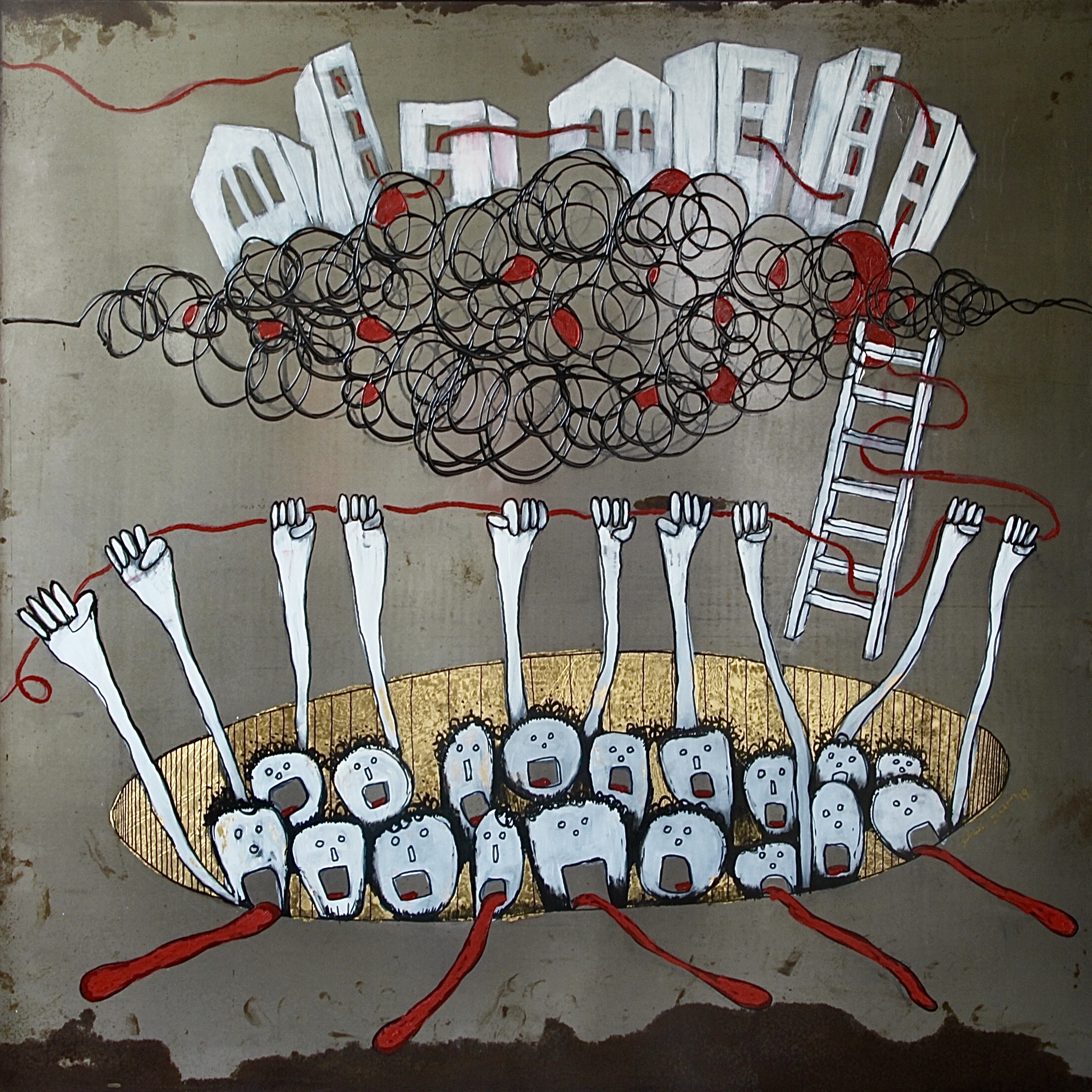

On Lebanon today

“Although Lebanon is going through extremely tough times, I believe things will definitely get better, maybe not in the short term, but I am sure Lebanon will experience a rebirth. We just need to remain positive because everything is bound to change. Nothing lasts forever.”

On life

“Human life is simple. Enjoy each day. Death is the only truth. Accept it.”