HOME has a tradition of showcasing Lebanese families, or what might be considered clans, that share the same name and heritage, often uniting under an association in the family’s name, like the Ma’lufs, Osseirans, Skaffs, Chehabs, Sinnos, Hamadehs, Bustros, and Daouks. In choosing an Armenian family, HOME sought to highlight their dual role as Armenians arrived in Lebanon relatively recently, and their families do not have the same historical timeline in the country. The choice of the Babikian family is primarily due to their dual role as active supporters of the Armenian community and culture in Lebanon as well as active participants in the social and political life of the broader Lebanese society.

The Armenian Church

We begin with a brief introduction to the Armenian Apostolic Church because it has played such a central role in maintaining Armenian culture in Lebanon and is so important to the story of the Babikian family.

Celicia Catholicosate headquarters in Antelias

Celicia Catholicosate headquarters in Antelias

Early in my research for this article, I came upon the word Catholicosate and mistakenly assumed it had something to do with the Catholic Church. Both words are, in fact, derived from the Greek Καθολικος, meaning “wholeness.” For Christianity in general, it historically referred to the “universal” Christian church and only came to be used to distinguish Catholic from Orthodox Christians after the schism of 1054, long after the Armenian Catholicosate was established.

The Armenian Apostolic Church, the world’s oldest national church, is the church of most Armenians. It is not affiliated with the Catholic church, but it is an Orthodox church of the Eastern rite that is shared with the Coptic and Syriac churches. The first Catholicosate (the headquarters of the church) originated in Armenia, but subsequently moved in the 10th century to a region in Southern Turkey close to the Syrian border formerly known as Cicilia. When a new Catholicos was again elected in Armenia in the 15th century, rather than dissolve the Catholicosate in Cilicia, the Armenian church came to have two headquarters.

With the ethnic cleansing and genocide of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century, the Catholicos of Cilicia and his entourage were forced to abandon their HOME in Cilicia in 1921, taking with them whatever ecclesiastic artifacts they could save. The Cathicosate moved to various locations in Cyprus, Syria, and Lebanon, and in 1930 it found a permanent HOME in Antelias, Lebanon at the location of what had been an orphanage established in 1922 by the American Committee for Relief in the Near East for survivors of the Armenian genocide. This important center has been headed by Aram I Keshishian — the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia of the Armenian Apostolic Church — since 1994, and has dioceses in Middle Eastern, European, as well as North and South American countries.

Khatcher Babikian of Adana

It is within this context that we begin the story of the Babikian family in the city of Adana, in the heart of Cilicia. The Ottoman millet system, an independent court of law pertaining to personal law, allowed each religious community to enjoy considerable autonomy. Armenians generally studied in their own community schools, but were otherwise integrated into Ottoman society. Khatcher Babikian, born in 1860, studied at the Armenian College of Adana, learning the French and Turkish languages on his own. This allowed him to serve as court secretary before he obtained a law degree from the Istanbul University Faculty of Law. He was successful as both a lawyer and a businessman in Adana.

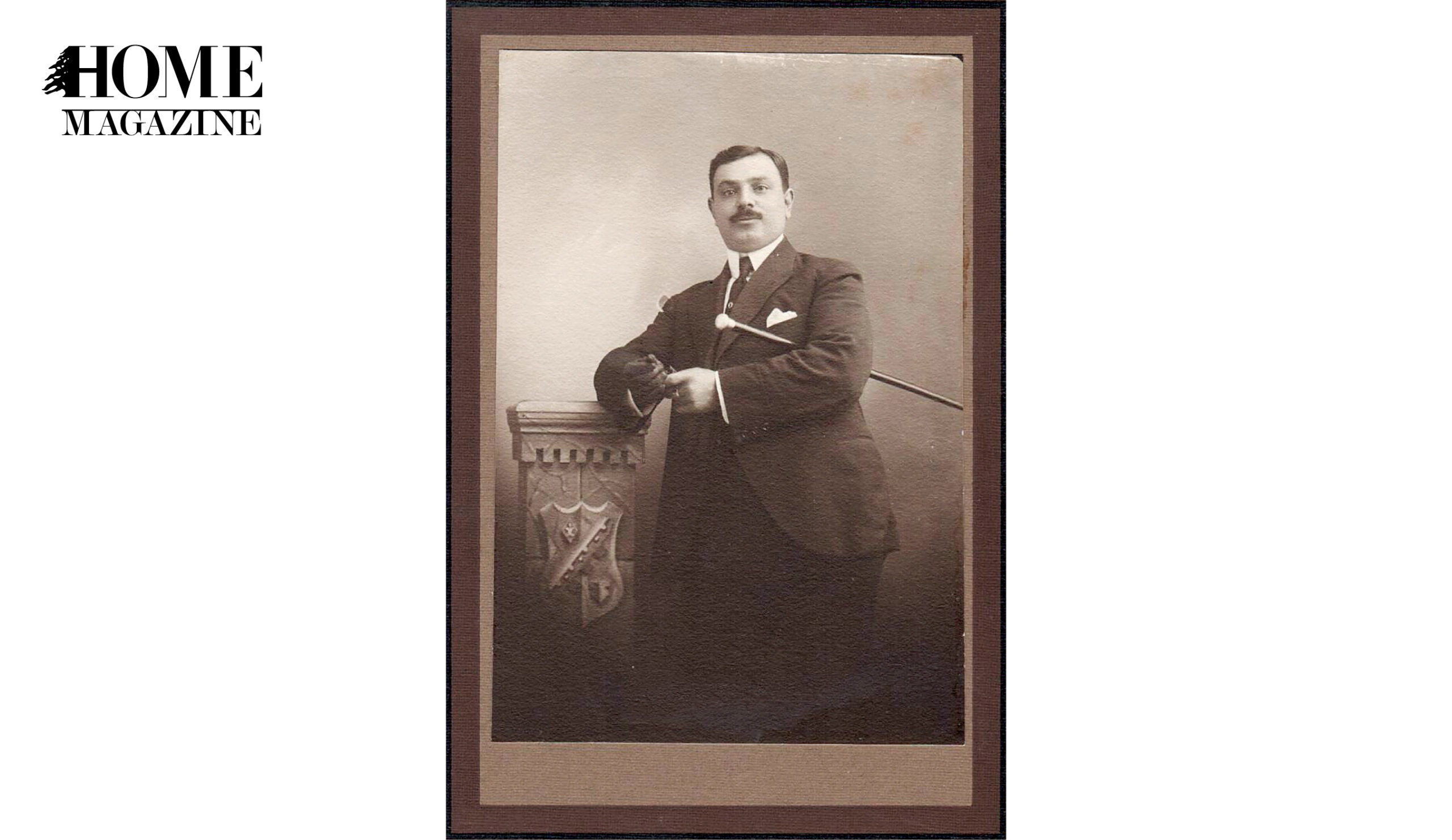

Diran Babikian

Khatcher’s son Diran Babikian was born in Adana in 1887. He studied at Armenian and non-Armenian educational institutions in Adana. He was pursuing a law degree in Switzerland when the Young Turks overthrew the government in Turkey in 1908. He celebrated the coup, believing this would usher in a new era of liberty and equality for all, but soon after he learned of the massacre of 15,000 to 30,000 Armenians in Adana in 1909 (including one of his uncles). His father Khatcher died in Adana in 1911 while Diran was still in Switzerland.

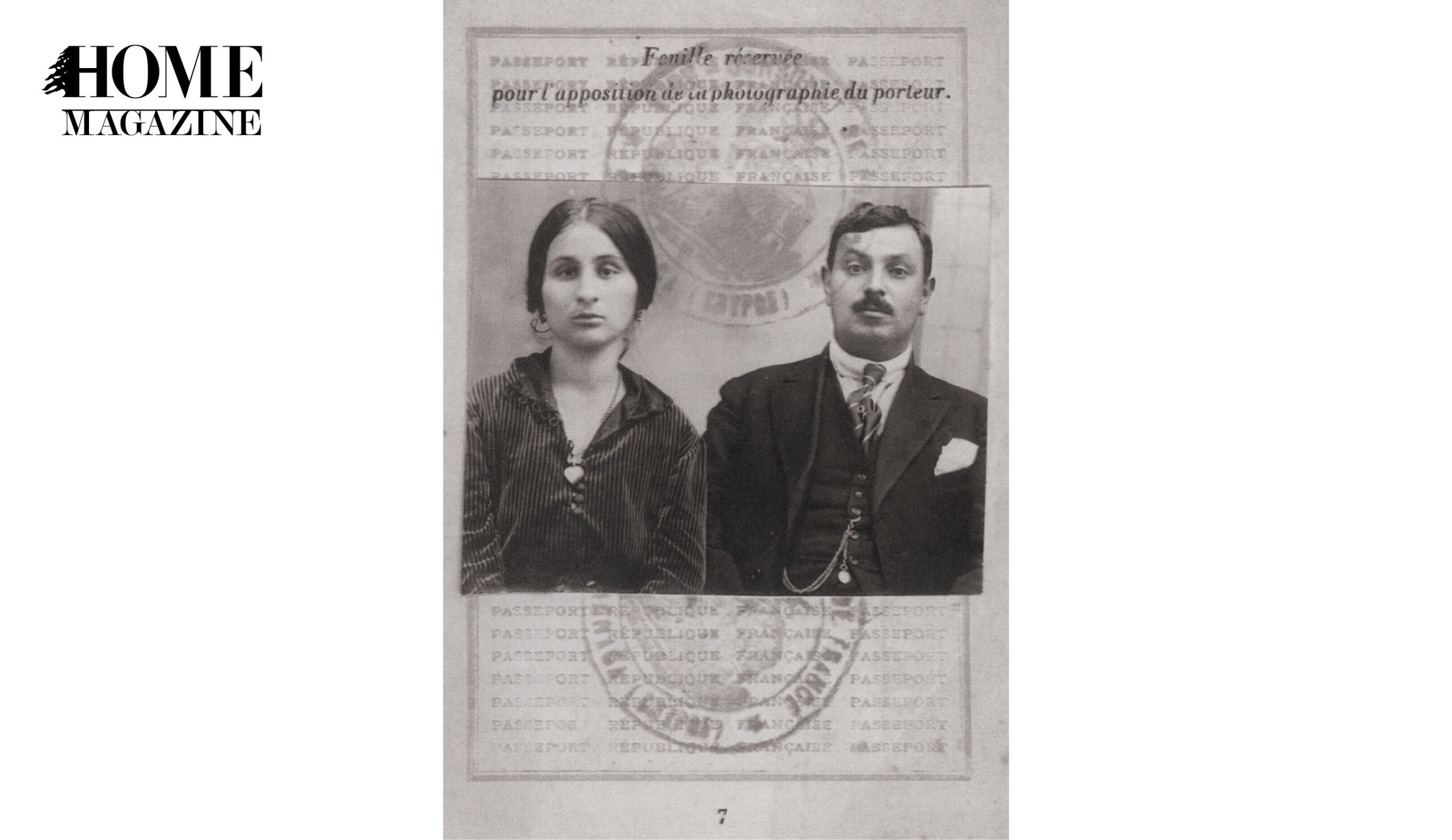

Diran and Yeranouhie Babikian passport photo

Diran and Yeranouhie Babikian passport photo

Hoping that the Adana massacre was an isolated incident, Diran returned to the Ottoman Empire in 1911 after completing his studies and enrolled at the Faculty of Law of Istanbul to study Ottoman jurisprudence. He graduated in September 1912 and returned to Adana where he practiced law and engaged in various business ventures. He was also involved in Armenian patriotic activities and was part of numerous Armenian charitable associations.

Diran became the official interpreter of the Italian consulate in Adana which opened in 1912, serving as an official liaison between the Ottoman State and Italian nationals in Adana. This position gave him protection, preferential treatment, and territorial immunity for himself and his possessions and Italian citizenship for himself and his family.

His position changed drastically, however, when Italy entered World War I against the Ottoman Empire. At the same time, the political and social situation of the Armenians deteriorated, and in 1915 the Ottoman government decreed the deportation of all Armenians from the country. Diran and his family narrowly escaped being killed, and initially fled to Aleppo. The extended family of 32 was allowed to settle in Homs where they remained until the end of the war, but Diran felt the need to flee to Zahlé in Lebanon whose governor and police were Christians.

In 1916, Diran spent a year in Souk el-Gharb, Lebanon, where he taught Turkish at the American School as required by all schools in the Ottoman Empire. Afterwards, he returned to Zahle, then Aleppo, and at the end of the war he traveled back to Adana which was then under French mandate. In 1920, Diran married Yeranouhie Semikian, the daughter of a wealthy Armenian family from Adana. Her family moved to Larnaca, Cyprus, and Diran and his wife joined them. This is where his first son Khatchig was born in 1922.

Meanwhile the French gave up their mandate on Cilicia, forcing the Armenians to leave the region permanently. The family again moved to Aleppo and then to Paris where a commission composed of French, English, and Italians was formed to evaluate damages suffered by their nationals during the war. In time, Diran was paid an indemnity, though far less than the losses he had incurred. His daughter Irma was born in Paris. He decided to move to Beirut via Marseilles where his second daughter Aida was born and where he learned soap making. He used the money from the indemnity to invest in a soap factory; in June 1929 they arrived in Beirut. This trip decisively settled his family in Lebanon where his second son Ara was born. By then, Lebanon had become an important refuge for Armenians, and was made even more significant in 1930 with the establishment of the Catholicosate headquarters in Antelias, a northern suburb of Beirut.

In Lebanon, Diran became a member of the National Patriarchal Assembly of Beirut which established an association funded by donations from Armenians in the United States to help students from Adana complete their university studies. He was also a volunteer member of the Legal Council of the Armenian Prelacy to help Armenians with legal concerns.

Diran Babikian

Diran Babikian

In 1939, at the onset of World War II, Italy sided with Germany. The French security services in Lebanon imprisoned Diran and his son Khatchig as Italian nationals, holding them in a camp in Syria. More than a month later they were released but were detained again when the British and Free French Forces of General Charles de Gaulle occupied Lebanon. While many Italians were sent to Africa where most of them perished, Diran and Khatchig were released but were required to check in periodically with the police until the end of the war.

Throughout his time in Lebanon, Diran had various business ventures and served as a lawyer, retiring in 1963.

Khatchig Babikian

Diran’s oldest son Khatchig began his schooling at the Brothers of the Christian Schools. He continued his studies at the Italian Boys School of Beirut where he recalled feeling out of place, not being Italian like the majority of students, and not having Armenian classmates. He obtained the diploma of the Italian State (Maturità Scientifica) in June 1940, but was then imprisoned with his father, as mentioned above. After his release, Khatchig followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, studying law at the Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth (USJ).

With Lebanon’s independence, Arabic became the only official language of the newly established country. Even though he’d been offered a position in France, Khatchig decided to stay in Lebanon. He spent a year intensively studying both classical and Quranic Arabic, thus acquiring his seventh language after French, Armenian, Italian, English, Latin, and Turkish. His mastery of Arabic was so remarkable that he was often acclaimed, and is still remembered, for his eloquence as an orator.

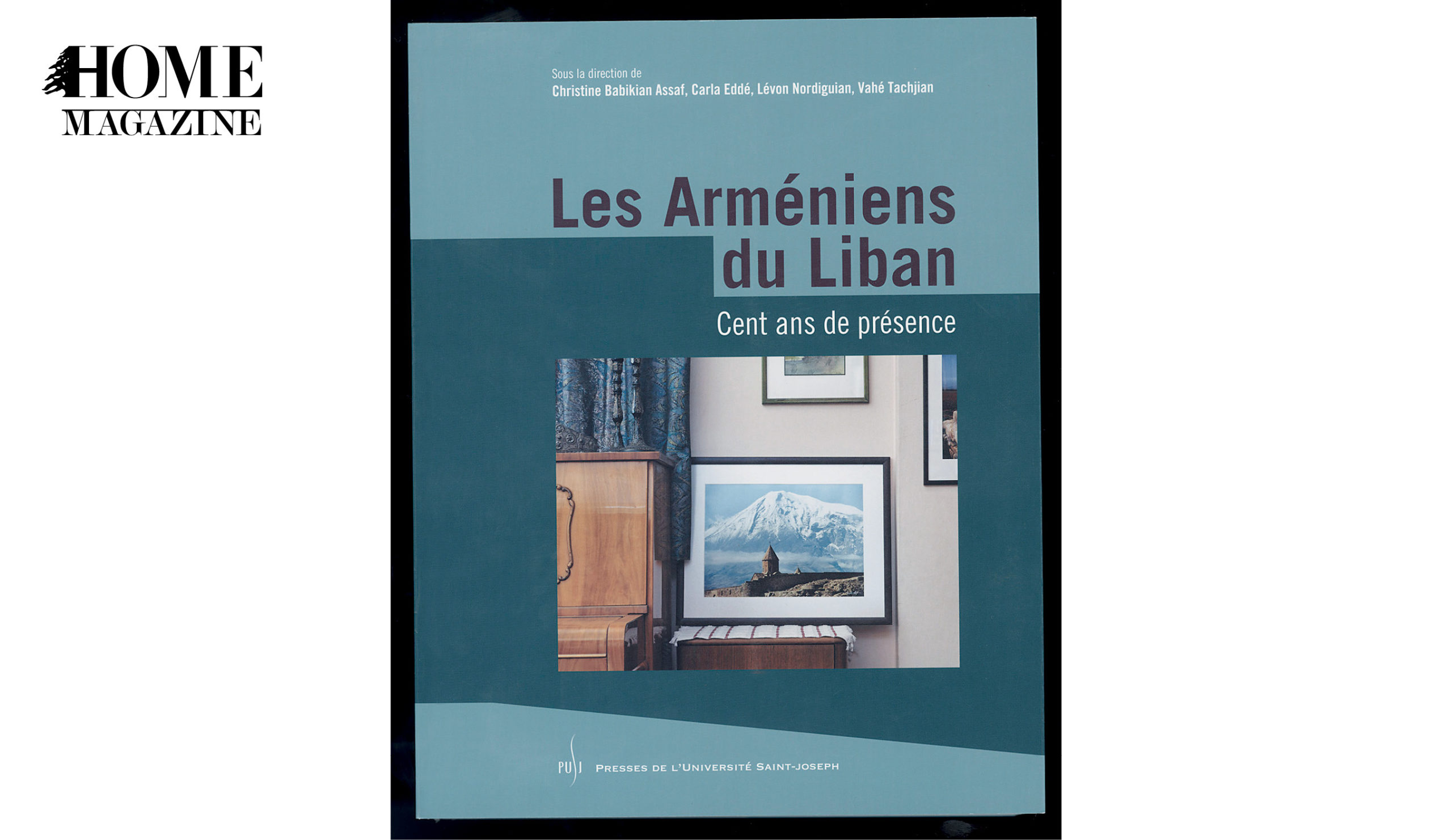

Les Arméniens du Liban Cent Ans de Présence, Presses de l’USJ, Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth

Les Arméniens du Liban Cent Ans de Présence, Presses de l’USJ, Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth

In 1956 he married Marguerite Hajjar. A year later, he entered political life as a member of parliament and remained a member until his death in 1999. While he was always supported by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Tashnag) party, he never joined as a member and thus was an independent parliamentarian. Throughout his political career he championed three main causes: integration of the Armenian community in Lebanese politics, justice and social equality, and administrative reform. He held numerous ministerial positions including administrative reform, public health, tourism, information, planning, and justice.

In the midst of Lebanon’s Civil War, he was a founding member and first secretary general of the World Council of Islamic-Christian Cooperation established in 1984 to promote peaceful coexistence between communities.

And on many occasions, he represented Lebanon in international forums and particularly in the International Association of Francophone Parliamentarians in which he was elected vice president twice, first in 1982 and again in 1997.

Khatchig Babikian and Khoren I Paroyen – Catholicos (1963-1983)

Khatchig Babikian and Khoren I Paroyen – Catholicos (1963-1983)

In his community, Khatchig held many leadership positions in support of the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. And from 1956 until his death in 1999, he served as the legal counselor of the Catholicosate. He particularly supported the building of the Leylavan 272 housing units in Fanar to resettle low-income Armenians who had been living in the slums of Quarantina. He was also a founding member and chairman of the Armenian Higher Committee for the Economic and Social Recovery of Lebanon, which was responsible for the repair of more than 2,000 housing units, and assistance to schools, churches, and needy victims of the Lebanese Civil War.

Khatchig was a major philanthropist during his lifetime, making important contributions to his parish church and the Catholicosate. And in memory of his wife who died suddenly in 1985, he created the Margot Babikian Foundation for Music with the aim of encouraging young Lebanese musical talents. Indeed, Khatchig was a great music lover and played both the violin and the piano. Before his passing, he laid the grounds for the Khatchig Babikian Foundation to help needy Armenians in the areas of housing, education, and health in Lebanon and abroad and to benefit Armenians in humanitarian, educational, and cultural projects. This foundation is administered jointly by the Catholicosate and his five daughters.

The Babikian legacy

Since this is an article on the Babikian family and not just Khatcher, Diran and Khatchig, it is important to consider the family’s legacy after Khatchig’s death in 1999.

While Khatchig’s five daughters (Reine- Marie, Christine, Anita, Carole, and Nicole) cannot carry the Babikian name into the next generation, they certainly have carried forward the family’s commitment to education, social justice, Armenian culture, and Lebanese society. Together they manage the Khatchig Babikian Scholarship Fund to provide financial aid to Armenians studying law and other subjects at USJ.

On an individual level, Reine-Marie, who studied law at USJ, worked in the Leylavan Committee founded by her late mother as well as the Armenian Relief Cross. Christine earned her Ph.D. in history and teaches and serves as Dean of the Faculty of Humanities at USJ. Much of her research has been related to the history of her family and other Armenians. Anita pursued a career in banking and management consulting.

Khatchig Babikian with French President Chirac

Khatchig Babikian with French President Chirac

She is an active supporter of Camp Haiastan, an Armenian summer camp in Massachusetts.

Carole studied political science at the American University of Beirut (AUB) and is active in civil society, currently heading Achrafieh 2020, an initiative started in 2012 to improve the quality of life in that neighborhood of Beirut. She’s an active member of the Jebid Association for needy children in Lebanon and a member of the committee running the Aram Bezikian Museum for the orphans of the genocide.

Nicole earned a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from AUB and later earned a diploma in translation from USJ. In Boston, she has spearheaded diverse charitable initiatives in the Armenian- American community, including the St. Stephen’s Armenian Elementary School, YerazArt (an organization helping young musicians in Armenia) and the Mirror Spectator (an English language Armenian weekly newspaper).

While none of the five daughters attended Armenian day schools, they were grounded in the Armenian language and culture through Armenian summer school, the church, and other Armenian social institutions. All of them feel a strong sense of their dual Armenian and Lebanese identity. Only one sister and one brother of their grandfather Diran came briefly to Lebanon and then settled respectively in England and France.

Khatchig Babikian’s first electoral campaign

Khatchig Babikian’s first electoral campaign

Khatchig’s brother Ara managed the family plastic factory in Beirut in partnership with his sister Irma who studied law. His older son Hrair (Harry) is a successful businessman in Belgium. Harry’s son Ara, now 21, is the namesake for the family line. Khatchig’s brother Ara’s second son Diran, who is single, now manages the family plastic factory in Beirut. Khatchig’s sister Aida was a pharmacist by profession. Her four children grew up in Lebanon but emigrated to France and Belgium during the Lebanese Civil War.

Conclusion

The Babikian family clearly cannot be viewed as typical Armenians in Lebanon. While they suffered the same tragedy of displacement and genocide under the Ottomans, they did not arrive destitute, as so many others did, because of the indemnity Diran was able to obtain as an Italian citizen. They also benefited from a long family history of education in both Armenian and non-Armenian institutions, and a combination of legal and business acumen. They have strongly supported Armenian institutions through their service and philanthropy while integrating fully into the larger Lebanese society, making important contributions to Lebanon’s social, economic, and political development.

Sources of this article:

Articles by Dr. Christine Babikian based on the detailed memoirs of both Diran and Khatchig Babikian, discussions with Khatchig Dedeyan (chancellor of the Catholicosate), and Christine, Carole, and Diran Babikian, online articles and references, and the book “The Armenian Church” by Aram I. Photographs taken from the Babikian family Archives.

For more info: https://www.facebook.com/christine.babikian.3