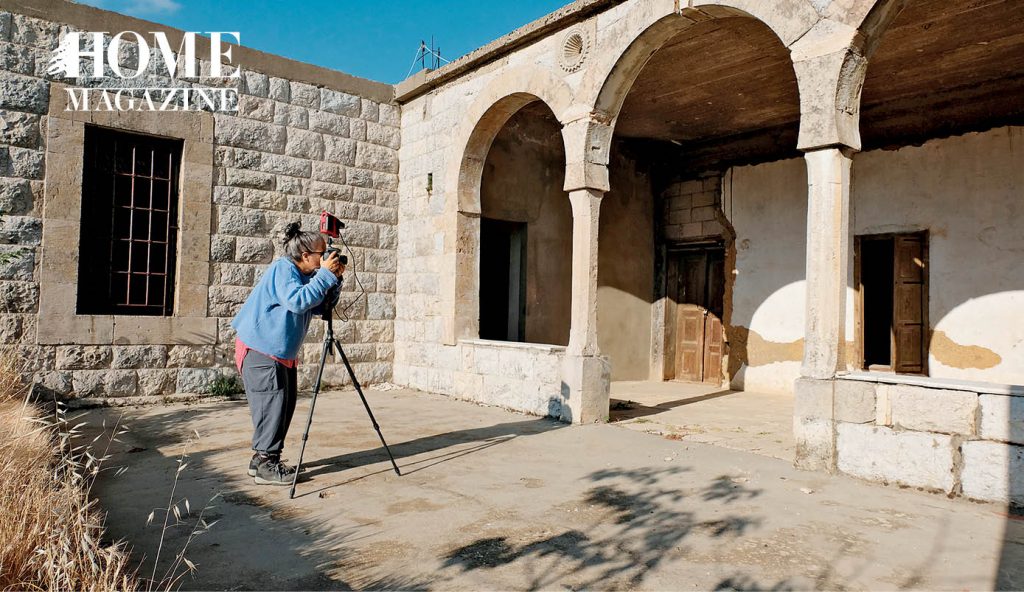

Photo by: Lama S. Riman

In the small town in New England, U.S.A., where Lebanese-American artist Andrea Shaker grew up, the local fire station tested its alarms at noon. “We lived across the street from the station so the alarm was quite loud. For me, the siren was part of an overall sense of comfort, something mundane that happened every day,” she said.

A Palestinian friend who grew up in Beirut was visiting one day when the noon alarm went off. She had a panic attack. For her, the high-pitched wail resonated with gut-wrenching sounds of 1980s wartime Beirut and the fear she had felt, Shaker said.

Today Shaker is an artist who experiments with images and sounds to evoke experiences and feelings. Although she never lived through war herself, she wanted to know how to “evoke a sense of empathy for those types of situations from a distance.”

She also explores the concept of HOME. “As an Arab-American, I am interested in a tension between a lived understanding of real HOMEland (the U.S.) and an imagined HOMEland (Lebanon),” she said. “With my photographic work and multimedia installations, I speak to an imagined HOMEland as an elusive place that is at once comforting, while creating a perpetual state of mourning.”

She draws on explorations of her Arab-American identity and the differences of how HOME is understood in America versus in the Middle East. And she ponders where her understanding of her Arab identity came from — her grandmother’s stories of Lebanon, images on the evening news?

Photo by: Andrea Shaker

Shaker was very moved by the late Lebanese-American journalist Anthony Shadid’s memoir, “House of Stone,” about how he went back to his ancestral HOME in Lebanon and rebuilt it. Shadid explained that the Arabic word “bayt,” meaning “HOME,” goes well beyond the actual structure. It conjures up ideas of family and longing. “It very much resonated with my own experience,” said Shaker.

“While this was my first time in Lebanon, on many levels it felt as a return.”

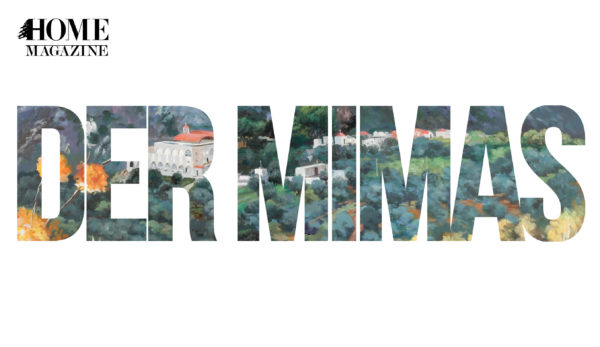

Although Shaker has spent years using her talents in photography, film and storytelling to consider her relationship to Lebanon, she had never been there — until 2017, when she visited Ma’asser el Chouf, the village of her grandmother’s stories and the scene of her latest project, “on bayt.”

Acclaimed artist creates empathy

Shaker’s work has received significant attention in the United States and abroad. Her photography has exhibited nationally and internationally, including solo and group shows in Minneapolis, Chicago, New York and Glasgow. Her award-winning experimental film work has screened at regional art festivals, and her creative nonfiction has been published in Women, Citizenship, and Photographies (Liverpool University Press, 2016).

A professor of art at the College of St. Benedict | St. John’s University, a nationally recognized liberal arts college in Minnesota, she teaches computer art, photography and mixed media installation.

In 2014, her experimental film “HOME. not HOME” was showcased by Twin Cities Public Television and won a MNTV 2014 Award. Informed generally by the Lebanese wars of 1975 – 1990 and 2006, and the incursions into Gaza, the film portrays HOME as both a place of comfort, and a place of war and confinement. It creates a sense of foreboding by juxtaposing calm interior views and sounds of domestic life with distant alarms.

“Since I was a young girl, I longed to visit Lebanon.”

What Shaker enjoys most about experimental film is “that one can be transported from one place to another.

…I hope that in this genre a level of empathy may be derived,” Shaker said in an interview on Twin Cities’ Public Television.

Shaker was the featured artist at the Altered Aesthetics Film Festival in Minneapolis in 2016, which premiered her performance piece, “on silence.” The film, accompanied by spoken word, and live violin and derbeke music, reflects Syrians’ mourning the loss of HOME and HOMEland and considers how images, moving and still, mediate our understanding of others’ trauma, creating an illusion of intimacy through the safety of distance.

Photo by: Lama S. Riman

Coming HOME to Lebanon

Shaker made two visits to Lebanon in 2017, 10 weeks in the winter and seven weeks in the spring. “While this was my first time in Lebanon, on many levels it felt as a return,” said Shaker. “Since I was a young girl I longed to visit Lebanon, especially Ma’asser el Chouf.

“Growing up, I would listen to the stories my grandmother told about life in the mountains of Lebanon. She told wonderful stories that evoked beauty. I imagined the olive trees and stone houses,” Shaker said.

“She even notices she looked like many others in Ma’asser el Chouf.”

Three of her four grandparents were from Ma’asser el Chouf or nearby.

Her paternal grandmother was from South Lebanon but spent some years in Ma’asser el Chouf before emigrating. All four of her grandparents left Lebanon and settled in the U.S.

The purpose of her visit, at least professionally, was to work on her new project, “on bayt.” It would include a short experimental film and a series of still photography. She explored the spaces of her paternal grandparents’ house, and the stories, real and imagined, that addressed how HOME is a container for individual, family and collective histories.

In the house, “I felt an absence emanating from the walls,” said Shaker, “and with it came whispers of histories, of stories, and the space for new stories to coexist with my older imagined stories: my grandmother baking bread, my grandparents tending to the farmland, my cousins playing in the winding streets.”

Some of the questions Shaker asked through the work were: How are understandings and experiences of bayt transformed (or not) through major events, such as war, displacement and emigration? How does one person’s memory become another’s imagined memory? How does the memory of an individual become a community’s memory?

Photo by: Andrea Shaker

On a personal note

On a personal level, her questions were more practical. Which house was my grandparents’? Who are my relatives? Do I feel at HOME here?

The answer to the last question is a definite yes. After two weeks in Lebanon, she wrote in her blog, “I have been met with Lebanese hospitality — a generosity of spirit that is unparalleled.”

Lebanese welcomed her into their HOMEs and hearts, she said. Through conversations with them, she often discovered relationships — “our grandfathers were brothers, our grandparents were friends, we are cousins … .” She even noticed she looked like many others in Ma’asser el Chouf.

One evening after dinner in the HOME of the village mayor and his wife, Shaker told them, “I feel at HOME here.”

“You are at HOME,” he said.

For more info:

http://www.maasserelchouf.org/beta/

http://www.csbju.edu/art/faculty/shaker

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wXNhieMOp6g&t=1255s