Photo essay by Aia Dakdouk and Sandra Whitehead

An-Nahar, one of Lebanon’s most influential daily newspapers, is 85 years old. It is considered Lebanon’s “paper of record.” American- British author and journalist Charles Glass, who specializes in the Middle East, called An-Nahar “Lebanon’s New York Times.” Its archives’ tagline is: “The memory of Lebanon and the Arab world since 1933.

What many don’t know is that the newspaper’s offices themselves are a living memorial to its martyrs and a museum of its history. At the same time, it is still an active newsroom, where journalists report both for the paper and for annahar.com, the online version launched in 2012.

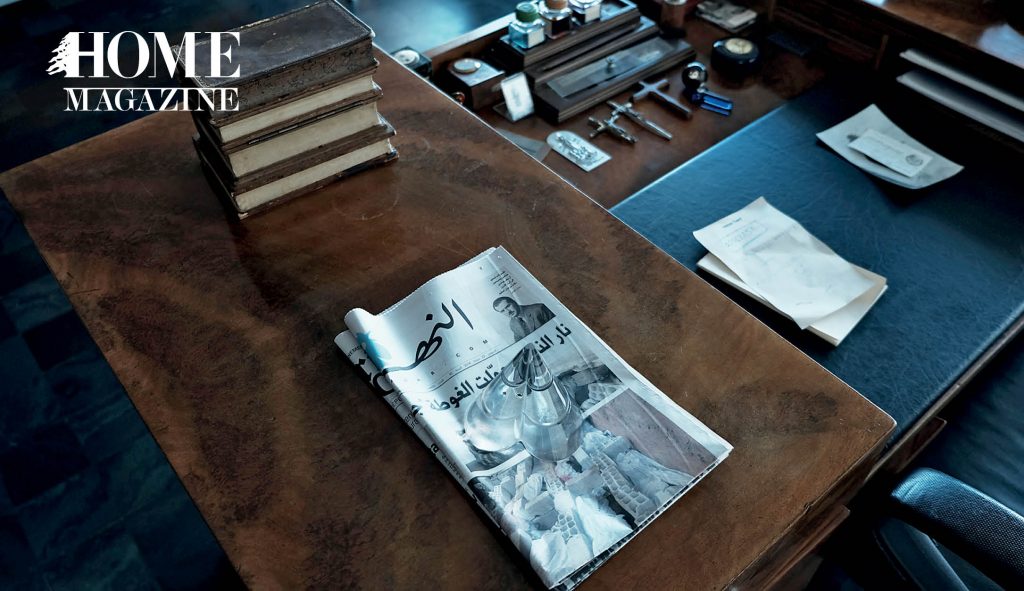

Inside the tall glass tower at the northwest corner of Beirut’s Downtown, known as the An-Nahar building, Gebran Tueni’s desk is frozen in time. A slip of paper with handwritten notes, a business card and a small stack of books sit just where they were on Dec. 12, 2005, the day Tueni was killed by a powerful car bomb near his HOME in Beit Mery. Every morning, a new issue of An-Nahar is placed on his desk, replacing yesterday’s news.

Beyond Gebran Tueni’s office is the office of his daughter, Nayla Tueni, the newspaper’s deputy general manager. Nayla Tueni marks the fourth generation of her family to work for An-Nahar.

Dec. 12, 2005

Gebran Tueni returned to Lebanon from Paris, where he had been in self-imposed exile because of numerous death threats. Optimistic about a moment of calm after a series of attacks against journalists and politicians, Tueni returned to Lebanon on Dec. 11, 2005, the day after his father Ghassan was honored for his press activities by French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin.

On the morning of Dec. 12, Ghassan Tueni received the news that his only surviving son was murdered. The 80-yearold Tueni returned to Beirut. An-Nahar spokesperson Ayad Wakim recalls: “He was a rock. Of course, the mood at the newspaper was catastrophic. Gebran’s father stepped up and took on the responsibilities. He told the staff, ‘He was my son. Nobody will love him more than me. We must carry on our mission. Tomorrow, An-Nahar will be published. No tears. Gebran is not dead because we shall continue his work.’”

An-Nahar, founded by an Orthodox Christian family, has been known to have a liberal editorial line and links to the Christian community. Since 2005, many associate it with the March 14 political bloc. However, Wakim says, “We did not follow March 14; we have long had our positions. March 14 followed us.”

Yet, An-Nahar always provided space for a plurality of political positions. In the 1950s and ’60s, Ghassan Tueni famously opened his opinion pages to a variety of viewpoints. Tueni’s office was, in celebrated historian and journalist Samir Kassir’s words, “a meeting place for the Arab establishment, which used it to make and unmake governments, and the intelligentsia.”

In his book Beirut, Kassir describes the Beirut of the 1950s and ’60s as a journalist’s paradise, a place where communication was unhampered and information readily collected. Political exiles from neighboring countries “enriched and complicated Beirut’s intellectual life. They lived in permanent contact with journalists and editors, whether they drank with them in cafes or deliberately sought them out in their offices.

“As governments in other parts of the region took steps to shackle public opinion, and many times physically to lock up its spokesmen, the newspapers of Beirut had come to represent the free Arab press.”

Four Generations of Tuenis at the Helm

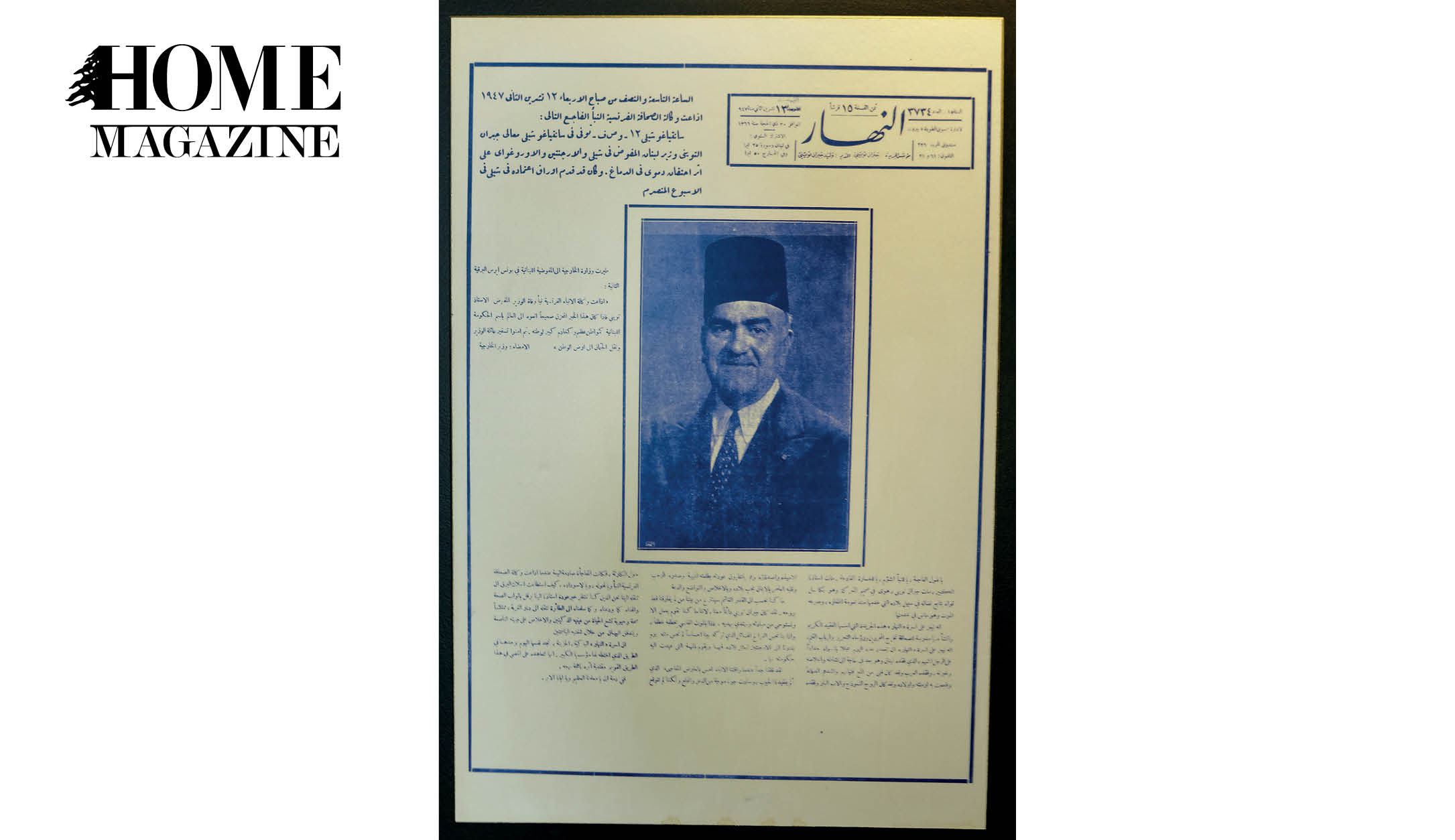

• Gebran Tueni founded An-Nahar in 1933.

• Ghassan Tueni took over in 1947, when his father died. An-Nahar became the most authoritative and credible paper in the Arab region.

• Gebran Tueni served as editor-in-chief from 2003 to 2005, when his life was cut short. His father Ghassan took over again until his death in 2012.

• Nayla Tueni is the current deputy general manager of An-Nahar. Nayla is a journalist and a member of the Lebanese Parliament, like her late father Gebran had been.

Ghassan Tueni’s office

An-Nahar’s first location was on Rue Hamra. “Gebran Tueni wanted to create a symbol of An-Nahar’s standing, and Downtown was on fire; it was the place to be,” said Wakim. “The building was ready for the move in 2004. It is not all our building, we occupy two floors, but everyone calls it the An-Nahar building.”

On Nov. 13, 1947, An-Nahar mourned the death of its founder Gebran Tueni. He founded An-Nahar in 1933 and served as its editor-in-chief until his death.

Many prominent writers, scholars and politicians have written for An-Nahar, including novelist Elias Khoury, young Walid Jumblatt before he succeeded his father as the Druze leader, a young Amin Maalouf, columnist Michel Abu Jawdeh and the late historian, writer and political activist Samir Kassir.

“Gebran Tueni used to go to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Important journalists, presidents, world leaders and big shots of all kinds attend. Mr. Tueni was given a key chain with the chairs and the name of the sculptor, Monkith Saaid, an Iraqi artist who had fled to the U.S. to ask for political asylum. Mr. Tueni looked him up and told him, I will invite you to Lebanon to create a big version – and we want to put our rooster on top.”

The rooster has been a symbol of An- Nahar since the 1950s. An-Nahar means “the day” in Arabic and in many a Lebanese village the rooster announces that a new day has arrived – a fitting symbol for Lebanon’s premier daily.

From 2008 to 2011, An-Nahar awarded courageous Arab journalists with the Tueni

International Award, a statue with a fist holding a fountain pen that appears to drip blood.

“When Samir Kassir was assassinated,” Wakim explained, “Gebran Tueni and 50 other journalists walked behind the coffin, raising their pens to the sky. The blood-colored ink

flowing from the pen, journalists in Lebanon pay for their freedom of speech with

their blood.”

Pour Gaby

En ce lieu indécis à l’heure des draps humides du matin au souffle gentil

Le bric à brac des mots rangés à l’envers dans la nuit frappe à la porte d’une image.

Alors le petit jour a glissé sur des rails ses pieds nus en couleurs.

Et c’est pourquoi les fleurs nous tombent encore des yeux après la mort du feu.Nadia Tueni; Le 12 Aout 1970

For more info:

For more info:

https://www.annahar.com

http://archives.annahar.com.lb/@NaylaTueni