Tom Young adopted Lebanon as his HOME

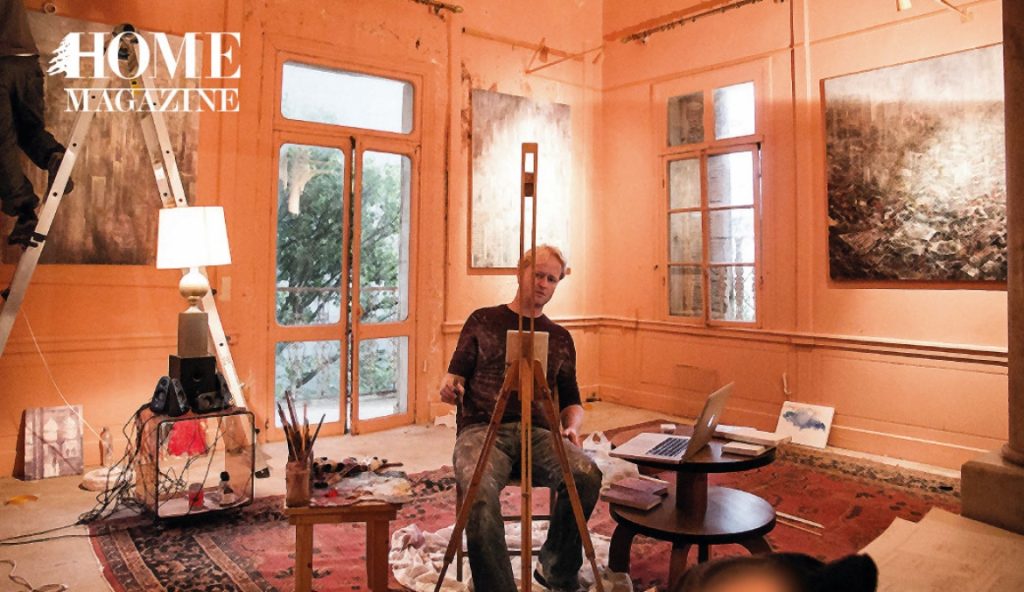

With a fleck of blue paint in his bright blond hair and a black t-shirt and blue jeans covered in the paint smears of a thousand different colours, British born Tom Young looks every bit the hardworking artist that he is as he welcomes HOME Magazine into his latest studio space; Beit El Zaher. Tucked away in the quiet backstreets of Zarif and a relatively unknown building to many people who live in Beirut; Beit El Zaher has a rich heritage that has had a profound effect on the history of Lebanon.

Tom Young’s Lebanese story started when he was living in London. His Lebanese car mechanic, longing for pictures of his HOMEland, commissioned Tom to paint a series of landscapes. Shortly before the start of the 2006 war, Tom made his first trip to Lebanon. “I just absolutely loved it. I felt immediately at HOME here. It combined the things that I loved about other countries. Places like Morocco, India and Turkey, but also Italy, the south of France and Spain. At the same time it was completely unique.” He completed his commission which received high praise from his HOMEsick mechanic.

“Lebanon combined the things that I loved about other countries. Places like Morocco, India and Turkey, but also Italy, the south of France and Spain. At the same time it was completely unique.”

Tom continued to work on commissions, but when gallery owner Aida Cherfan bought 12 of his paintings, he realised that this was going to be his big break. With the opportunity to do a large solo exhibition in Beirut, it made sense for him to leave the UK and move to Lebanon. He moved in 2009 and had his first exhibition in 2010.

By 2011 Tom’s art had started to change. “I felt more inspired here than I had felt anywhere else… I think that it probably sparked off some emotional triggers for me.” Tom’s work now took on a more confrontational attitude; dealing with issues such as memory, absence and the contrast of joy and pain. Tom was hoping to push his art in directions that it hadn’t been before. While Tom found this new style of his to be more enjoyable for him to create, it did have a fairly major drawback. Gallerists were less enthusiastic and refused to exhibit these new paintings.

“I felt more inspired here than I had felt anywhere else.”

Having trained as an architect, Tom fell in love with the mix of French and revivalist Ottoman stylings that can be seen in many of the Beirut’s older buildings. This aesthetic joy was mixed with sadness when he saw the dilapidated condition that many of them were in.

At the outbreak of the civil war, waves of destruction hit the city in the form of mortar shells and gunfire. When the war finished, the tides of violence went out, but a new wave of destruction soon engulfed the city in form of mass development. As majestic family HOMEs that had stood for a century were torn down, modern towering edifices of steel and glass replaced them; although arguably required, they sucked part of the soul, character and heritage from the city. Few of these older buildings now survive, but a quiet revolution is growing to ensure their survival, and Tom Young is one of the people at the forefront of this fight.

Facing rejection from the city’s more traditional galleries, Tom was searching for a venue for his work. “And then I walked past Villa Paradiso, which at that time was empty and derelict. I got in touch with the owners and proposed to them my idea about turning it into a venue for my art, and they loved it.” Villa Paradiso was the perfect venue for Tom. It had the ability to highlight the need of preservation for the city’s older buildings; and the unique quality of the space twinned perfectly with his new style and ideas of confronting issues that affected the city and the individual. By all measures, the exhibition, which was titled Carousel, was a huge success, and Tom knew that this was the future for his work. When the exhibition wrapped up he started looking for somewhere new.

The Rose House in Manara was a building that Tom had seen and photographed on his first trip to the country. Standing high on a hill and looking out to the sea, the Rose House is known for its captivating pink walls and the crumbling distressed facade. Tom knew that it would be the perfect venue for his next exhibition. The building had recently been bought by a property developer. When Tom approached him, he was more than happy to allow Tom to use the space as his studio and host an exhibition. If Villa Paradiso was a success, then the Rose House broke all records. Attracting over 6000 people over the 3 months that the exhibition ran, it brought a new life to the building. As well as exhibiting paintings, they had video installations, dance recitals, DJs and book clubs. The exhibition garnered international attention and attracted new vigor to the fight for Beirut’s architectural heritage.

For Tom’s latest project, he has taken a sideways step. While it still features one of Beirut’s grandest and oldest residences, it is as much about the stories that the building gave life to as much as, if not more, than about the building itself. The architect in Tom adored the building, but it was its history and the stories that he fell in love with. “It’s a stunning interior. Just beautiful, and the garden is gorgeous. It doesn’t seem right that such a beautiful place is closed to the public. I wanted to do a project where people in the city could have the chance to come inside and see this beautiful place. When i found out more and more about the history, I was amazed.”

For his exhibition, Tom is exploring the stories of this house and the role it played in the shaping of the Lebanese nation. As well as a number of paintings of the interiors and exteriors of the building, he is also producing a number of portraits of former residents and regular visitors, most notably the British Ambassador from 1941-44 General Sir Edward Spears. Heralding the heritage and history of the building is a chance for people to reappraise a man who had “been forgotten, not just in Lebanon, but also he’s been forgotten by the British. This man deserves recognition and more respect.”

Beit El Zaher has two floors and the exhibition will also be split in two. While the top floor will be occupied by Tom’s painting, the ground floor will be taken up by artworks created by children who come from Dar Al Aytam’s orphanage.

Dar Al Aytam are the current residents of Beit El Zaher. They have been operating since 1917, when they cared for orphans who had lost their parents during the First World War. Since then they have been providing care and support for Lebanese orphans and mentally and physically challenged children. For Tom, the children are the second part of this exhibition and equally as important. “This project isn’t purely nostalgic… We’ve come up with the concept of working with the children. Perhaps not on the political history so much, but the history of the architecture and the beauty of nature that surrounds the building. It’s very much about the future as well. Going forward are going to be making the Lebanon of tomorrow.” While Tom is playing the role of teacher to the children, he admits that it is in fact him who has learnt a lot from them and their free form styles, untainted by experience.

Tom recognizes the shift in ideas his work has taken. It’s a shift that has come about not just from the building which he currently calls his studio, but also from the work that Dar Al Aytam does. “The Rose House paintings were permeated by a feeling of sadness and loss, because that is what the building seems to embody. For this project, the paintings are about a sense of joy, movement, celebration, and freedom… In a way this is a happy story because the building survives…. And the lives of these kids are being supported… The paintings should express some of that joyful energy.“

For more info: