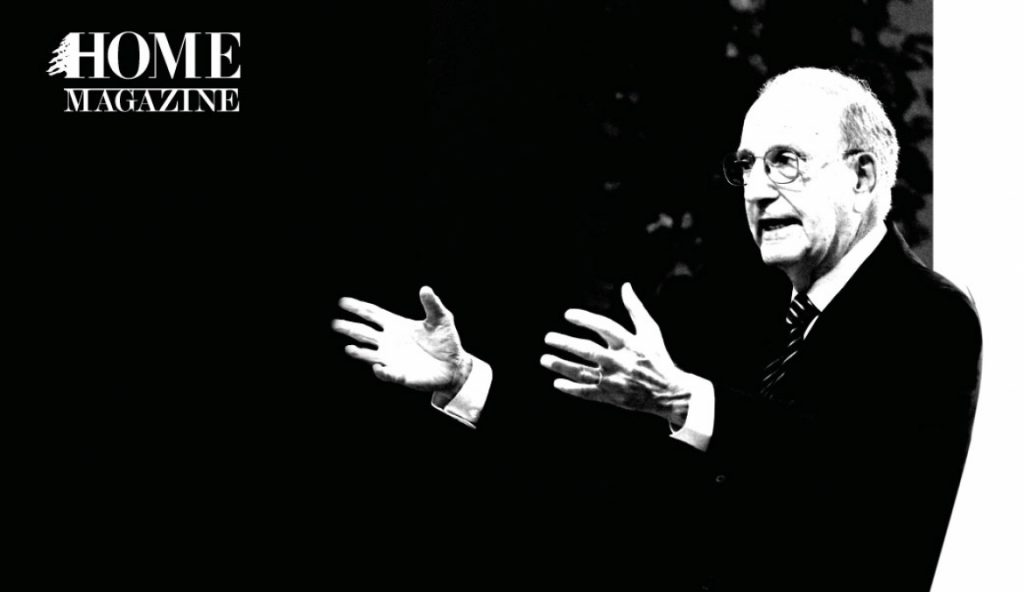

Photo by Dan Johnson, Marquette University

One of the most respected leaders in America, former Senate Majority Leader and peacebuilder George J. Mitchell helped achieve the Good Friday Agreement to bring peace to Northern Ireland and served as Special Envoy to the Middle East. He has also served as chairman of the Walt Disney Company. Mitchell talked with HOME about his Lebanese heritage and his remarkable life.

“Everything I am is drawn from my parents and particularly from my mother,” said the Honorable George Mitchell, whose mother immigrated to the United States from Bkassine, Lebanon, in 1920.

Former U.S. Senate majority leader and special U.S. envoy George Mitchell, who spent six decades as one of America’s most respected political leaders, spoke in October at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, at the invitation of MU’s Center for Peacemaking, and with the support of Richard Abdoo, a prominent American business leader of Lebanese heritage. During his visit, HOME Magazine interviewed Mitchell about the influence his Lebanese heritage has played in his life, his thoughts on today’s Middle East, the U.S. presidential elections and America’s future.

Mitchell’s remarkable career in public service includes 15 years as the Democratic senator from Maine, with six years as Senate Majority leader, from 1989 – 1995. He played a leading role in the Northern Ireland peace negotiations that led to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and he served as the U.S. Special Envoy for Middle East Peace from 2009 – 2011. In addition, he was the main investigator for two important reports: one on the Arab-Israeli conflict in 2001 and the other on the use of performance enhancing drugs in U.S. baseball in 2007. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1999.

In addition to public service, Mitchell was chairman of the Walt Disney Company and is the author of five books, with the sixth, A Path to Peace, which is about the Middle East, that came out at the end of November.

Pat Kennelly, director of the Marquette University Center for Peacemaking, said the center eagerly invited Mitchell because his “work has modeled how world leaders can use nonviolence and negotiation to resolve seemingly intractable conflicts. For students, Mitchell is an example of the perseverance needed and the fruits that can be produced when one dedicates their life to peace.”

GROWING UP – A MOTHER’S INFLUENCE

Dapper in his dark blue suit, crisp white shirt and maroon tie, Mitchell, 83, smiled warmly at the memory of his mother. “She was without a doubt the biggest influence on me. All that I have done, all that I am, I owe to my mother,” he said.

Mitchell told his mother’s immigration story in his memoir, The Negotiator. His mother, born Mintaha Saad, left Bkassine, a small village in the mountains of south central Lebanon, when she was 18. Upon her arrival, Mintaha called herself “Mary.”

“She had never before left Lebanon. She could not read, speak or understand a word of English,” Mitchell wrote. The family had arranged for her to meet a potential suitor in Paris, during the journey, “but … it was clear all along what she wanted was to get to America, where she would join her sisters and be free to make her own decisions.”

In the interview with HOME, Mitchell said he learned values — hard work, generosity and respect for others — from his mother’s actions more than her words. “For all her adult life, she worked the midnight shift, from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. in a textile mill, all the while raising five children. After working all night, she was HOME in time to get us off to school and she’d have supper ready when we returned HOME. She would tuck us in at night.” In his memoir, he described her as “tireless and energetic, full of love and life.”

The Mitchells lived in Head of Falls, a small triangle of land along the banks of the Kennebec River in Waterville, Maine. It was what Mitchell called “the lowest rung on the ladder” for immigrants. “As families established themselves, they moved up and out of Head of Falls,” he said. In the early 1900s, immigrants from what is now known as Lebanon moved into the area. “By 1933, when I was born, almost all the families living there were Lebanese immigrants.”

Mitchell’s mother demonstrated the famous Lebanese hospitality, he said. “You couldn’t leave our house before you had a proper meal.” He recalled the story of the pair of Mormon young men who knocked on the Mitchell door to share their message. Mitchell’s mother insisted that they stay for dinner. She invited them back the next week and the next. They became regular guests.

“Lebanese hospitality: You couldn’t leave our house before you had a proper meal.”

“She didn’t speak much English and barely understood what they said. She understood their purpose but couldn’t understand their arguments. They talked with her about religion and she talked with them about food.”

Describing himself as the runt of the family, Mitchell recalled his mother’s admonitions to him to drink goat’s milk and study. She later attributed his success, whatever it was, to all the goat’s milk he had consumed.

Mitchell grew up hearing his mother’s stories of Lebanon. She grew up in a Maronite village where the church was the center of life. “She was deeply religious and her faith was total, unquestioning,” he said. “She lived the gospel. She was extraordinarily generous. After she stopped working, she attended church every day, living its message in her daily life.”

Lebanese values were also passed down from his father. Although of Irish blood, Mitchell’s father was adopted by a Lebanese family. “It was the practice at the time for the nuns who operated the orphanage to take the children on the weekends to Catholic churches throughout northern New England. After Mass, the children were lined up in the front of the church. Any person attending Mass who wanted to adopt a child could do so simply by taking one by the hand and walking out,” Mitchell wrote in his memoir. John and Mary Mitchell, who had immigrated from Lebanon and assumed the surname “Mitchell,” took his father HOME. The family moved to Waterville, Maine, where “baby Joe” grew up, met and married Mary Saad.

Mitchell’s father worked as a janitor at Colby College. Although he never had the opportunity to pursue education himself, his father was an avid reader, said Mitchell.

Mitchell also learned to empathize with those who struggle financially by seeing his father out of work. He struggled with a loss of dignity when he did not have work, Mitchell said. “I still get angry when I hear blanket condemnations of the unemployed. I know that most of those out of work would prefer to be working.”

Following the example of hard-working parents, Mitchell worked all of his life. He worked as a truck driver, an advertising salesman, a dormitory proctor and a fraternity steward to pay for his studies at Bowdoin College. Later he worked full time as an insurance adjuster while attending Georgetown University Law School at night.

Through his parents’ examples, their appreciation of the opportunities in America, and his mother’s stories of life in her Maronite village, Mitchell said he grew to love both America and Lebanon. He pointed out a favorite anecdote at the end of the memoir that he said captures that point:

When we were growing up (my mother) often said to her children, softly and with nostalgia, “You should see Lebanon. It’s so beautiful. The air is pure, the water is clean, the mountains, the forests, even the flowers smell better. Oh Lebanon, my Lebanon.”

After arriving in the United States at the age of eighteen, she returned to Lebanon only once, late in her life, after my father had died. My sister Barbara accompanied her as they returned to the village of Bkassine, where they attended a reception and dinner with relatives and friends in the house in which my mother had grown up.

Late in the evening, my mother was asked to say something. According to Barbara, my mother stood, paused, looked out at the large, happy crowd, and, with great emotion and a broad smile, said, “You should see America. It’s so beautiful. The air is pure, the water is clean, the mountains, the forests, even the flowers smell better. Oh America, my America.”

ON TODAY’S MIDDLE EAST

Mitchell was appointed by President Obama as the U.S. Special Envoy for Middle East Peace from 2009 to 2011. His latest book, A Path to Peace: A Brief History of Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations and a Way Forward in the Middle East, was released by Simon & Schuster at the end of November.

Achieving a peace agreement between the Palestinians and the Israelis has been elusive, Mitchell said. “Our objective has been to get a peace treaty. Twelve presidents, 20 secretaries of state, innumerable envoys like myself have all tried and failed. But we have contributed towards what I think is progress.

“The pursuit of peace is so important that every step I think puts another brick in the building, the edifice dedicated to peace,” said Mitchell. “In the pursuit of peace, you can’t quit at the first no, at the 10th no, nor at the 20th no.”

On Syria, he said, while the immediate future in Syria looks grim, “I believe there is no such thing as a conflict that can’t be solved. Peace can prevail,” he said.

ON THE AMERICAN ELECTIONS

Speaking to faculty, students and visitors at Marquette University about the recent U.S. presidential elections, Mitchell said “one of the great tragedies” of the presidential campaigns was that “major issues are simply not being addressed. It’s almost all personal attacks, back and forth,” between Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton and Republican nominee Donald Trump.

He said politics today has grown more contentious. Mitchell recalled “the good old days” when he was Senate majority leader and Republican Senator Bob Dole was the Senate minority leader. They disagreed passionately about issues, but were friends at the end of the day. “We never had a harsh word between us.” It is possible to have a good working partnership with people who don’t share all the same views, he said.

On the other hand, “it is absolutely shocking” that there were 17 candidates for the GOP presidential nomination and “every single one denies the existence of climate change and global warming.”

“It is a denial of science and knowledge that is wholly unjustified,” he said. “They know better. They have to know better. The science is overwhelming. Yet our country faces, the world faces, a profound threat. And you have people saying it’s a hoax.”

ON THE FUTURE OF AMERICA

Mitchell’s advice to the new U.S. president?

“Our country faces many challenges. I believe we are still the most fortunate people who ever have lived,” said Mitchell. “Even though we have progressed so dramatically, a young person growing up today has less chance to get ahead, especially those in rural America and minorities.”

“We’ve got to do more to make the aspirations of all young people realized. We have more creation of wealth, but it is not distributed.”

Comparing the present to the industrial revolution at the beginning of the 20th Century, Mitchell said, “The progress is uneven. No rational person would argue we are worse off, but people who lost jobs are hurting. You don’t stop progress, but you mitigate the harm. We have to help those people who are victims of the revolution.”

To the students present, Mitchell advised, “What really matters in life is working for a cause that is bigger than yourself. Success ought to broaden your impact beyond yourself.”